I only got to work with Joe Flummerfelt once, for one incredible 45-minute segment of one rehearsal on one ordinary day. He was visiting my teacher, who had been a student of his, at Northwestern University, and Dr. Nally had asked him to conduct a rehearsal of Brahms’ Schicksalslied (“Song of Destiny”) with us.

It was…incredible. I have sung for wonderful conductors before, but this was like nothing else I’d ever experienced. It was like a door somewhere inside him opened, and Brahms just sort of spilled out into the room and flowed all around us, or like he was the painter and we were the canvas and he was just splashing Brahms all over us—like we were not just the artists, but we were also the art itself.

(I also remember, with the part of my mind that stayed calm and rational and in the room, that he sang with us; not the actual vocal parts, but just sort of an under-the-breath vocalization of the sweeping lines he was conducting. It was a little distracting, to be honest—but it also was sort of lovely, and endearing, and it reminded me of Glenn Gould.)

Mostly what I remember was that it felt like magic, like all the mental and rational score study and stick and hand technique we spend our time as conductors focusing on was merely incidental, the box we build to hold the real art, the music and the line and the spirit and the love. And that the important part of what we did as conductors and educators and makers-of-music-with-others didn’t live in that rational world at all. I knew this already, but it was something I’d always felt a little sheepish about, or kept kind of quiet, because it felt like something we weren’t supposed to admit out loud. But here he was—out loud, witnessing it for all of us. I’ve never forgotten it.

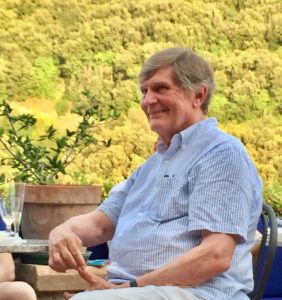

Joseph Flummerfelt passed away last Friday night. Somehow this giant in the choral world isn’t as much of a household name among the rest of the musical community in general as I would have thought—like Robert Shaw, for example (who was Maestro Flummerfelt’s teacher), whose name is widely known. But “Flum,” as his students called him, had an amazing history and life. I don’t need to recap his accomplishments—those were not what made him extraordinary. (You can read about them here, though, in this tribute posted by Rider University and Westminster Choir College, or here, in his obituary in the New York Times.) Accomplishments are seldom what make any musician extraordinary. But those rare few whose magic is so great, whose ability to touch something indefinable and essential calls out to the rest of us, are like magnets, pulling us closer. And Joe was one of those magnets. The outpouring of memories from his students and colleagues in these days since we lost him makes that absolutely clear. He touched many lives, and he will continue to do so—that’s what master teachers do; they continue to touch us long after they are gone.

Joseph Flummerfelt passed away last Friday night. Somehow this giant in the choral world isn’t as much of a household name among the rest of the musical community in general as I would have thought—like Robert Shaw, for example (who was Maestro Flummerfelt’s teacher), whose name is widely known. But “Flum,” as his students called him, had an amazing history and life. I don’t need to recap his accomplishments—those were not what made him extraordinary. (You can read about them here, though, in this tribute posted by Rider University and Westminster Choir College, or here, in his obituary in the New York Times.) Accomplishments are seldom what make any musician extraordinary. But those rare few whose magic is so great, whose ability to touch something indefinable and essential calls out to the rest of us, are like magnets, pulling us closer. And Joe was one of those magnets. The outpouring of memories from his students and colleagues in these days since we lost him makes that absolutely clear. He touched many lives, and he will continue to do so—that’s what master teachers do; they continue to touch us long after they are gone.

So why am I posting this here, on a blog that is supposed to be aimed at practical formation for pastoral musicians?

Most of those who know me know that while I have one foot planted firmly in the world of liturgical music and pastoral ministry, the other lives solidly in the arena of choral conducting and art music. This is probably connected to the fact that I tend to view music ministry less as being about directing a small choir singing for an audience of assembly members than about being the person directing the big choir made up of everyone in the room. (Who needs an audience, right?) Maybe I just need the reminder, or want to say out loud, that while the nuts and bolts skills involved in music ministry are of course the key foundation of everything we do, whether as choral musicians or pianists or organists or cantors or whatever our medium of music-making might be, the real movement of the Spirit lies outside of what the skill set can accomplish, and that we as ministers are more than just craftspeople—we are still artists, we are still required to keep our hearts and spirits open and vulnerable and turned outward to the people we serve. Joe Flummerfelt knew this, and he saw his work as the work of holiness; he knew that his work in a concert hall or rehearsal room was no less sacred or worshipful than what happens in any church on Sundays, that the movement of the Spirit is everywhere, whether he phrased it in those terms or not.

Every year at Westminster Choir College, where Professor Flummerfelt conducted and taught for 33 years, one faculty member would give a “charge” to the new graduates at their commencement. A colleague and friend was gracious enough to share his charge to the graduates one year (I believe it is from 1983?) with me. I would like to quote a portion of it here:

“I think one of the great sicknesses of the human condition today is the extent to which we are estranged from ourselves, the extent to which we clamor after gurus of whatever ilk, be they TV preachers, political demagogues, paperback therapists, or the requisite name on the back side of our blue jeans, to tell us who we are, what to believe, what to think, indeed, even to tell us that we exist. Far too many of us look outside ourselves for our center, for our sense of being. And far too many of us are often fooled by the façade or by the label, and believe a thing is what it looks like or what it is called rather than being able to perceive what it is. Lacking connection with our own centers, we lack the capacity to penetrate to the center of that which is about us. Even in our own profession, we are often lured by virtuosity for its own sake, which, though dazzling in appearance, is in fact full of sound and fury and signifies nothing because it springs from no central human or spiritual impulse…Touching center is not an easy thing. But if we believe that it exists, if we believe that the Holy Spirit does dwell within as well as without, if we learn to nurture calm, to be still, so that we can hear the voices within, if we are willing to risk stripping away all of the protective layers with which we have separated ourselves from our core, then the inside and the outside can become one. Then creativity can flow, then the gift of intuition is freed and we are able to see the unity of things, feel the impulse of things…As we grow in love for and acceptance of the life within us, we will become ever more in tune with and resonators for the life about us. We become instruments of the Holy Spirit, and the music we make touches the hearers at their own center and the people with whom we work are helped to connect with the source within themselves. For me that is our calling, as human beings and as musicians. And if we accept that charge, then the glory of God will be ever more manifest in the lives we lead and the music we make.”

–Joseph Flummerfelt

Next blog post I will go back to the more “normal” stuff of liturgical and musical formation. But for this moment, at the beginning of this Lenten season of renewal, this challenge to artists from an artist is one I challenge all of us to carry with us.

Peace be with you, Maestro. Eternal rest grant to him, Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him.

–Jennifer

Header Photo by Carol L. Jenkins

Photo by Steven Ryan

Beautifully seen, heard, felt, remembered, and described, Jennifer. Thank you for this tribute to a giant among musicians whose music and spirit touched thousands, and through those people, touches millions and generations. Whether as a student and singer who worked with and made music with Dr Flummerfelt (as I did) or as a listener at concerts or hearing recordings he made, our lives and spirits are richer for what he elicited and shared with everyone.

Thank you, Jennifer, for your beautiful thoughts about our beloved Joe. And yes, I do remember the intonations that accompanied his spiritual flow of music. I stood directly in front of him in Westminster Choir in the 70s and was graced with his spirit on a daily basis. That spirit now lives in all of us to carry on.

A lovely and perceptive tribute to a man I sang for every day for three years, and whose insight and example I carry with me always.

Inside the front cover of my conductor’s score for the Faure Requiem lives this quote from Flum: “There is perhaps nothing more sacred in all the world than to make music with people you love.”

That was how he lived his life, whether he talked about it or not. It is his legacy to we who were fortunate to be his students.

Lovely and moving tribute. Joe became the music he conducted. It was always a startling transformation from watching him prepare, coach, cajole, discuss with and plan for his chorus, to actually sing a concert with the Westminster Choir, conducted by Joseph Flummerfelt. It was his spirit energizing his presence, most of all, that made the experience unique.

Wilbur, perhaps you know Jennifer? She sings with CSO and is one of the associate conductors of the chorus.

Thank you for this, Jennifer. The man had magic, no question about it.

Thank you Jennifer…he was a master teacher!