This past weekend, 22 people were murdered and dozens more seriously injured in a mass shooting that took place in El Paso, TX, the city where I live with my family and call home. The shooter was a lone gunman who traveled more than 600 miles to target and kill Hispanics in our city for fear of a “Hispanic invasion” of our country. The massacre took place at a local Walmart store on a Saturday morning, while people were buying groceries and families shopped for back-to-school supplies.

The shooter came from a Dallas suburb to do this evil deed, after having posted a hate-filled manifesto to his social media. The community was violated. Brutally, horribly violated in the worst possible way. A 15-year old high school sophomore, a young mother, her husband, a grandfather, a grandmother, and numerous others all with beautiful lives to live and loving families, all mowed down in an instant with bullets and a machine gun. While most of the victims were U.S. citizens, eight of them were actually Mexican citizens, not even from this country. They were not invading; they were going to go back home, to their own country, after shopping. This man wanted these people —who he did not know and who were not like him— to suffer, to pay the price of his anger and hatred, not knowing that they would have probably taken him in with profound kindness and compassion. That is the sad irony.

Border Reality

The community of El Paso is unique. It shares a border along the Rio Grande with the city of Ciudad Juárez in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. It is a peaceful, loving community. I can best describe the environment as insanely hospitable. Really! People routinely greet each other with kind, cordial (and actual!) dialogue: “Buen día, ¿cómo está?” or “Hola, ¿qué tal?” or “Con permiso, por favor, muy amable.” Children are regularly addressed as “mijo” and “mija” (“my son” and “my daughter”) by kind, though unrelated adults as an expression of care. There is a sense that if you were ever stranded and needed to knock on someone’s door for help, not only would you get that help, you’d probably get a fresh, hot, delicious meal and a place to stay for the night. This is a city of hospitality, warmth, and welcome, infused with a sense of family and neighborly love.

It’s especially hard for others in the U.S. to comprehend just what a safe place this border city is. You might ask, how can a city that shares its municipal and international boundary with one of the most notorious cities on earth, Ciudad Juárez, be so secure, when its neighbor is literally ravaged in crime and lawlessness? That’s the paradox, así es. To quote Bruce Hornsby, that’s just the way it is… in a good way. The violence to the South doesn’t spread across the border. El Paso reaps the benefits of a population that cherishes its peace and safety. The drug-driven activity of Ciudad Juarez remains over there or is transported to other U.S. cities with drug epidemics, bypassing El Paso, which is left largely untouched by these elements.

So much of the general population of El Paso is Hispanic, the great majority of Mexican descent. Spanish and Spanglish are primary languages alongside English for much of the population. Families share their lives on either side of the border. Tías, primos, abuelos, even padres may live on one side while children and other family members live on the other. They come and go from both sides, peacefully and as part of the daily way of life. They visit each other and celebrate cumpleaños, bautizos, bodas, or holidays as family. The economies are intertwined. Many El Pasoans —U.S. citizens—, make the daily commute to Ciudad Juárez to work in the sprawling auto supply manufacturing industry there; these are white-collar workers with engineering degrees. Likewise, many bright, talented young people from Mexico make the daily commute to the U.S. to attend the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). They pay their tuition like anyone else, enrolled as international students in this iconic institution of higher education. Afterward, they all return to their homes, whether on the U.S. or Mexican side, sometimes spending several hours in line to cross the 1/4-mile long, international bridge. That’s life here. And it is beautiful. And peaceful. And safe.

And upsetting to those who fear difference.

The particular store targeted by the shooter in El Paso was one that is but a few miles from the Mexican border. Mexican residents routinely shop at this Walmart because the selection of goods is greater and prices actually more affordable than what they can find in their own town. (Something you and I take for granted as we zip to the neighborhood market or superstore just minutes from our homes.) It’s worth the time and effort for them to go on an international journey just to do some routine shopping for household goods, clothes, and school supplies.

Turning to Prayer

In the wake of the tragedy, prayer vigils and rallies were scheduled. Memorials and funds were set up. Immediately, the city and community came together to grieve, find strength and solace, vent anger, and pray.

I provided the music at one impromptu diocesan-wide prayer service, hastily scheduled in the wake of the tragedy that same evening. I figured that plans were probably still up in the air with details. Sure enough, with such short notice and general city-wide chaos, the planners had not had a chance to think much beyond a time and location, so I came prepared to step in and ensure that music was part of whatever prayer took shape. I’m not even sure why I showed up, because all motions that day felt numbed; I only I knew that I needed to be at church in prayer with my community of faith and that we needed to sing.

Announced to begin at 7 pm, just 8 hours after the initial 911 calls were made, the community filed in that evening to St. Pius X church, quietly and still stunned. The beautiful church, where my wife and I were married, sits along the I-10 freeway, less than a mile from where the shootings took place. Fr. Michael Lewis, a native of El Paso and recently ordained, led a beautiful bilingual liturgy that both comforted and united all present through God’s Spirit and Word. We listened to readings, prayed our petitions, mustered strength to sing our grief, carried forth 20 candles for the deceased, and prayed a litany to the sacred heart of Jesus. The Gospel reading was from John 14: “Do not let your hearts be troubled, have faith [for] I am the way, the truth, and the life.” Media cameras clicked incessantly all throughout.

Fr. Mike’s preaching was impassioned, compelling, honest and raw. The disbelief and horror of the moment were still fresh on everyone’s mind. At one point he confessed to us all, “I’m barely holding it together here,” stating that afterward he was headed to the hospital to anoint the wounded survivors of the attack, some of whom might not survive. (Sure enough, two more victims were later added to the initial count of 20 deaths.) Yet, the principal message was one of love. Defiant love. Illogical, incredulous, unwithheld love in the face of hatred. Because God’s love will always overcome evil and violence, love was the key to unlocking our own comfort and healing. Powerful words. Tough message. Gospel truth.

Liturgy in Tragic Times

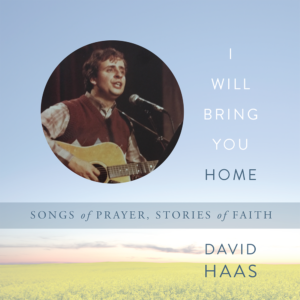

While strange to think of or somehow be focused on liturgy in the face of such unspeakable horror, I couldn’t help but be moved by the sight of this gathered assembly at the prayer service. It truly was the wounded, suffering body of Christ. As I entoned the opening strains of the hymn “You Are Mine” by composer David Haas, with its refrain that says “Do not be afraid, I am with you,” I heard the people singing. Emphatically, defiantly, gloriously singing. We were singing our sorrow, exasperation, confusion, and surrender that day. But we were also singing our faith, trust, gratitude and determination. As the document Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship reminds us, “Our participation in the liturgy is challenging. Sometimes, our voices do not correspond to the convictions of our hearts. Other times, we are … preoccupied by the [troubles] of the world” [Sing to the Lord, 14]. But it is Christ himself, whose body was brutally wounded and weakened, who invites us —each of us, personally— “to enter into song, to rise above our own preoccupations, and to give our entire selves to the hymn of his Paschal Sacrifice for the honor and glory” of our triune God.

From my vantage point as the lone musician, I looked out on the faces of the assembly. Further contemplating the sad events of the day. I recalled the section from Sing to the Lord which states, “Because the gathered liturgical assembly forms one body, each of its members must shun ‘any appearance of individualism or division, keeping before their eyes that they have only one Father in heaven and accordingly are all brothers and sisters to each other’” [GIRM, 95, as quoted in STL, 35]. That rogue thought led directly to this next one: “Why, O God, could not these words have fallen onto the ears and into the hardened heart of this evil shooter? Could not, even for him, a change of heart have taken place if only love had been given a place to take hold?” My head hung in defeat.

But then I looked at what was before me. People from all around the city were gathered in prayer. No matter our individual race, culture, language, or other external difference — we were and will continue to be brothers and sisters to each other with one Father in heaven. In this truth was revealed God’s grace. Amidst the profound sadness, a small but knowing smile formed.

To close the service, I led the well-known song in Spanish based on psalm 116, “Caminaré en presencia del Señor.” People sang with fervor, wanting their voice heard. With its verses that speak of anguish, sorrow, and falling into the snares of death, the refrain rang forth each time professing that we, together as the beautiful, multicultural and ever-hospitable community of El Paso, will indeed choose to walk in the presence of the Lord, in the land of the living.

And our light will shine forth in the darkness.

For we are #ElPasoStrong.

Let the church sing Amen! ¡Que cantemos Amén!

If you would like to give to the victims’ fund: please visit:

https://pdnfoundation.org/give-to-a-fund/el-paso-victims-relief-fund

If you would like to give to Annunciation House, which shows El Paso’s ongoing hospitality through its care and welcome for refugees and migrants:

https://annunciationhouse.org/financial-donations/

beautifully considered and written, Peter

Thank you for this beautiful and poignant reflection, Peter, and for helping us to remember how liturgy and prayer can guide us through the most challenging of times. Here at Assumption College in Worcester MA, we are adding a service/immersion trip to El Paso and Chaparral in May 2020 so that our students have the opportunity to see much of what you describe in this reflection.

Peter: I am immensely grateful that you and your family are safe, and so very sorry that you are face-to-face with the consequences of this horror. You are a beacon of hope in a dark time, and I’m honored to call you colleague and friend. Thank you for finding words. Thank you for your abiding presence.

This is a beautiful reflection. Thank you for being such an important presence in our lives during this trying time. It’s difficult ministering when you need to be ministered to yourself. Please take care of your self, so that you can take care of the others in the days to come. You are in all of our prayers.