Ministering through Music

Keyboard to Keyboard

¡Cantemos Amén!

First Communion Liturgies, Part II: “We’ve Always Done It This Way” (Pushing the Needle)

In the first part of this piece (found here), we talked about the mission and vision at the core of our work with children preparing to receive their First Communion: we are there to form disciples. As a part of that vision, it is crucial that we begin to look beyond the beauty and specialness of the day itself–though of course we do not forget it. We look forward and within, into the life and worship of the parish community and the wider Church of God–their fellow disciples in the journey, whose company they are preparing to join. We visited the idea of working intentionally, through repertoire choices and other aspects of the day, to link the First Communion celebration with the week to week and season to season life of the larger community.*

It is a process that takes planning and consistency, and each time I’ve been part of the process of shaping evolving norms and ways of thinking at parishes where I’ve ministered, there has been a mountain of cultural history (most often voiced as “but this is the way we’ve always done it”) to work through. History takes a long time to shape, and it will of necessity take a correspondingly long time to begin to shift. (If you are in a parish where this is not an issue, blessed are you among musicians!)

So, let’s look at just one of those ingrained cultural moments we so often seem to run into: the opening procession.

(Let me preface this with a disclaimer and a caveat. As one writing publicly about liturgical formation, and as one with advanced degrees, and who has taught liturgical/musical studies at the graduate level, please be assured that I do know the documents, I am familiar with the rubrics as well as the deeper theological underpinnings of the various rites, and given the choice I definitely prefer to take those as the starting point from which all else flows. In fact, there is a nervous little part of me right now going, “Oh no, what if my wise liturgical colleagues read this and hear me suggesting things that don’t necessarily fall in the liturgical best practices envelope? What if they see me openly compromising my Educated Liturgical principles? Will they take away my liturgist card?” But I am also very well-acquainted with the reality that not everyone in leadership in every parish has read and studied said documents, and that saying “This is what the documents say, so this is right and the way you’ve always done it is wrong” would be not only hurtful to one’s colleagues, but also ineffective in actually, you know, producing growth in the life-giving direction of letting the rich symbolism of the liturgy speak as it is crafted to speak. Sometimes being together is more important than being right. Sometimes we need to begin in a place we did not choose–but always holding the end in mind, and slowly help our communities move there.

In other words: ultimately, we have to Make It Work. End of disclaimer.)

Back to the opening procession. Almost everywhere I have ever been, First Holy Communion has begun with an elaborate and lengthy procession of all the children in their beautiful clothing, carefully spaced to ensure optimal visibility (and photographability). Music has usually been entirely instrumental, or has had the children enter to an instrumental piece followed by a separate opening hymn as the liturgical procession follows them. I can understand this, at least. In this beautiful moment, parents want to see their children walking into church; if there was ever a time when being buried in a worship aid is not a valid expectation, this is it.

However, in most of the places I have ministered, the catechetical teams have tended to a tradition of the children entering to Pachelbel’s Canon in D or the Trumpet Voluntary of Jeremiah Clarke or something of that ilk—music I mostly know, as I am certain do most others, from playing it for weddings.

Think of the imagery here: boys in suits and little girls in white dresses and veils processing into church to wedding processional music. Is this the image the Church calls us to in this moment? The Eucharist is its own powerful sacrament, one of the three sacraments of initiation; must we overlay it with such heavy imagery of another sacrament here in this moment? Are there other choices we might make, choices that would put the focus on the processional as the start of a wonderful and special eucharistic gathering, rather than as an “event” of itself?

For the moment, let’s assume that we do want an instrumental piece for the part of the procession where the children walk in (something I would not take as a given, and the documents certainly do not, but more on that later). What if we chose a piece of music that could automatically segue into a congregational piece, at the very least expressing in a concrete way that the children’s entry is part of the liturgical gathering?

Just as an example: for several years, at one parish, we played Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of man’s desiring” as the children processed in. (I am aware that this one also appears on many “Wedding Processional” lists in various places; in this parish, however, it was rarely used as such, and its relative cultural familiarity made it an acceptable substitute for the planners I was working with.) We then seamlessly segued into James Chepponis’s “Come to the Banquet”—a wonderful and lively song in G major compound time like the Bach–and all began singing together as the liturgical procession entered the church. Since this song was in our regular parish repertoire already, parents and children already knew its easily singable refrain by heart and could join in while the choir and cantors sang the verses.

I still kept thinking, though, of #31 in the Directory for Masses with Children, which reads: “The children’s entering in procession with the priest can serve to help them to experience a sense of the communion that is thus being created”–clearly an invitation to the children to enter not in a separate formal procession of their own, but with the ministers.

What if, instead of keeping these pieces separate, we instead blended the two pieces of music, shifting back and forth from “Jesu, Joy” to “Come to the Banquet” during the time the children were walking, slipping an instrumental verse and refrain of the Chepponis between statements of the Bach material? Musically as well as symbolically, this is far more aurally satisfying than simply playing through all of “Jesu Joy” three or four times in unceasing succession before shifting to the congregational song. (There were a lot of children.) While not perfect, and acknowledging that some people might be even more upset with disrupting the integrity of the Bach than the integrity of the should-be-sung opening of the liturgy, this solution honors the desire of those who hold onto “the way we always do this,” and at the same time achieves the sense of a unified procession linking the children, the ministers, and the Sunday liturgical experience. In future years, one might then consider singing those interpolated refrains…and then singing the verses…

It might take years to arrive where you are trying to go, but the final destination is worth it. Incremental shifts in practice like this one, over time, can continue pushing the needle further and further–in this case, from the original quasi-bridal procession of the children in pairs–with the goal of making this celebration feel like a joyful and celebratory eucharistic gathering of all the people of God, welcoming these little ones to the table for the first time.

I have also been in parishes where we did not assume that the opening piece had to be instrumental. One can have great success with a congregationally sung opening for First Communion, as long as it can be sung, by all, mostly from memory. A joyful Taizé ostinato like “Laudate Dominum” or “Let us Sing to the Lord!”—especially if they are already in the parish repertoire (and if they are not, it’s a good idea to get them there before introducing them at First Communion)—would be very easy to sing without programs, especially if a few minutes were taken at the beginning of the liturgy to teach the simple refrain to all those gathered and encourage them to take part in the singing. Consider “Uyai Mose/Come, All You People” in its new call-and-response setting arranged by Gary Daigle, a joyful song that can easily be sung by everyone without booklet in hand. It can be a wonderful thing for the children, who are often nervous as they enter the full church on this big day that they have been preparing for so long, to be surrounded and even embraced by the joyfully singing voices of their families, inviting them into the space on this day.**

Note too that choosing music from the regular Sunday liturgical repertoire, in addition to offering music that links the First Communion celebration to the Sunday liturgical practice of the community, renders unnecessary that most dreaded and love-of-music-killing phenomenon of many First Communion processes: the dreaded “Song Practice” where the children “learn their songs” for First Communion, and where the songs are often treated as another assignment or classroom-based lesson before they may come to the table. In a perfect world, Sunday Eucharist should be all the “song practice” they need. They, and we, are the same community–why would we choose music that obscures that beautiful reality?

One significant change that more and more parishes have begun to explore is to offer the option—or the norm—of having their children receive communion at the regular Sunday liturgies during the Easter season. In these communities, children might be scheduled for a specific day and time, maybe 6-10 per liturgy, and their reception at the table takes place literally within the Sunday community. Depending on how many children a parish is initiating, entire Easter season can become a time of welcome and celebration. This model bypasses many of the challenges presented by the separate First Communion liturgy on a Saturday, and it is a beautiful thing: this smaller group of children, with their parents and families all present (in this contexts we are not faced with “you can only bring as many family members as will fit in the pew” or ticket distributions to make sure everyone fits), can enter with the liturgical procession in the beginning of liturgy, and then can be be called up around the altar for the Eucharistic Prayer. They are welcomed to the table individually and by name, rather than as a whole “classroom” group. The logistics of planning and organizing, coordinating with catechists and clergy and music and liturgy departments, can be complicated especially early on, but once it settles into the rhythm of the community, it’s a truly lovely thing. (And, by the way, it also needs add no more than a minute or two to the total length of the liturgy.)

I have had the pleasure of witnessing and praying in this kind of within-Sunday-liturgy celebration several times. However, when I have tried bringing the idea back to the parishes I have served, it was generally met with horror and absolute resistance. A Sunday celebration, without all the children together, without the formal processional at the beginning and highly choreographed Communion procession–not to mention without the children’s group song at the end (a rant for another post)– represents a deep and countercultural departure from the way most of us (at least where I live) “have always done it.” The cultural history runs deep, and on some level we all instinctively know that to change the way we ritualize our most important life moments is to change who we are as a people. And that change cannot come until we are ready for it.

The opening procession is just one liturgical moment—but it is the first such moment in the gathering, and every moment is an opportunity. Every hymn or song we choose, every choice we make about sound or silence or movement, is going to speak volumes.

It is up to us to be awake and alert to what it is going to say.

I would love to hear about your creative approaches to First Eucharist in your parishes! Regardless of where you started and what traditions are firmly entrenched in your parish practice, how have you, through music, helped shift the needle toward a deeper connection with the ongoing life of the Christian community?

–Jennifer

*An increasing number of dioceses in the United States are shifting to the restored order of the Sacraments, bestowing the Sacrament of Confirmation prior to First Eucharist; this would of course shift the dynamic of how these liturgies are celebrated and merits a post all of its own.

**In fact, this very concept is what I express to the families and guests when I teach the opening song before the children come in: “The children are excited, but they are also a little nervous; as we welcome them to the table with us for the first time, let’s surround them with our voices, so that as they walk into church and down the aisle, they can feel and hear our love and welcome surrounding them, and we can help transform that nervousness into happy anticipation.” People who normally would not want to sing will sing when they are singing for their kids.

Body Mapping: with Bridget Jankowski (Sing Amen! The Podcast, episode 19)

Podcast: Play in new window

When I look back over the past few decades, it feels as though I have spent a huge portion of my life as a professional musician dealing with tension, pain, stiff shoulders, tendinitis, and all kinds of bodily aches. Most of my colleagues would say the same, I expect. It never occurred to me to wonder if they were optional; I thought that was just part of being a musician.

I had heard of Body Mapping, but I never seemed to find the opportunity to dig in and learn about it, or find out if it could help me. (I was too busy working, and practicing, and taking Advil for my aching joints and tension headaches.) Until last summer, when Bridget Jankowski, author of Body Mapping for Music Ministers, sat down with me one day during the 2018 NPM Convention in Baltimore, and taught me more about this remarkable practice.

This podcast episode is essentially a distillation of that conversation. Bridget’s work, and her book, talks not only about Body Mapping as a vehicle to increased clarity and efficiency (and decreased pain!) for the musician’s body as we make music, but also about how this practice can help deepen our awareness and focus as we perform our work as ministers. Our conversation quite literally changed almost everything for me about the way I conduct, the way I sing, the way I teach, and the way I work with my own choruses; it is truly amazing—and I’ll leave it there and let you listen, since Bridget explains it all far better than I can!

(And if this intrigues you even a little—Bridget herself will be speaking at the Raleigh NPM convention in a little over a week, giving one of the Mega-Breakouts. Please come see her in person and learn from a truly remarkable teacher!)

Music heard in today’s podcast:

As recorded on Vision, CD-295

Sing Amen! the Podcast, with Jennifer Kerr Budziak

Sound by Jim Bogdanich

Sing Amen! opening music: Promenade, by Bob Moore (from Let Every Instrument Be Tuned for Praise, CD-491, from Liturgical Suite #4, G-4789 ©GIA Publications, Inc).

Sing Amen! closing music: Amen, (from More Sublime Chant, CD-459, The Cathedral Singers, Richard Proulx, conductor. ©GIA Publications, Inc.)

Show By Your Life: A Conversation with Lori True (Sing Amen! The Podcast: Episode 18)

Podcast: Play in new window

Okay, it’s been a while since our last podcast! It’s good to be back.

Part of the learning curve for me with this site has been realizing when the crunch times come, so I can be ready for them…I’m just coming out of one of those crunch times, because in Publisher World, there is a big push about 6 weeks before all the big conferences, when all the projects need to go to press for printing. NPM is next month in Raleigh, July 16-19—and if you haven’t registered to go yet, please do consider it, because it’s going to be a great week.

(By the way: I will be one of the retreat leaders during the Pre-Convention events, for a retreat day for women on Monday July 15, working with Lorraine Hess, ValLimar Jansen, Meredith Augustin, and Sarah Hart. It will be a day of music and prayer and reflection, and you won’t want to miss it—I know it’s filling up fast, so while they will take onsite registration if there is still space, I’d recommend registering early.)

Anyway, a lot of stuff has gone to press in the last few weeks! New collections, books, Revival 2, new wedding music, Volume 8 of Paul Tate’s “Seasons of Grace” collection, The Organist’s Craft (the newest volume of the “As Found in the GIA Quarterly” series, which I edit), and of course Lori True’s new collection Show By Your Life, inspired in great part by the writings and words of Pope Francis.

That edition is in fact hot off the presses as I write this, and so it seemed like the perfect moment to release this podcast episode of a conversation I had with Lori last fall at the GIA Fall Institute, when this collection was in its early stages of development. Lori had just given a workshop addressing the importance of singing about social justice and letting the words we sing as a community address the very real concerns of our world today. She was kind enough to sit down and talk with me about her writing process and how she got here. It was a wonderful conversation, and here it is interspersed with excerpts from some of the songs from the new collection, as well as a few old favorites.

Enjoy!

Music heard in today’s podcast:

As recorded on Show By Your Life, CD-1054

I Send You with the Grace of my Spirit, G-9985

As recorded on Show By Your Life, CD-1054

As recorded on There is Room for Us All, CD-639

Prayers of the Faithful—Advent (from Cry Out With Joy, Year A, G-8481)

As recorded on Cry Out With Joy, Year A, CD-931

What Have We Done for the Poor Ones? G-6709

As recorded on There is Room for Us All, CD-639

As recorded on Show By Your Life, CD-1054

Sing Amen! the Podcast, with Jennifer Kerr Budziak

Sound by Jim Bogdanich

Sing Amen! opening music: Promenade, by Bob Moore (from Let Every Instrument Be Tuned for Praise, CD-491, from Liturgical Suite #4, G-4789 ©GIA Publications, Inc).

Sing Amen! closing music: Amen, (from More Sublime Chant, CD-459, The Cathedral Singers, Richard Proulx, conductor. ©GIA Publications, Inc.)

___

First Communion Liturgies, Part I: Mission and Vision

When my daughter was born in early May about 14 years ago, I remember a brief moment of feeling a little luxurious that I suddenly, for the first time in decades, found myself not at church on that first Saturday in May. (It was a very small feeling of luxury; on that first Saturday in May had probably not gotten more than an hour of sleep at a stretch in days, and if you’ve never done it, let me make you aware that those first days and weeks after childbirth are no walk in the park for the human body. I’m not sure I could have gone for a walk in the park at that point anyway.) Of course, it was not long before I realized that this also meant that every year on the Saturday nearest my daughter’s birthday I would be spending a large amount of the day at church—celebrating multiple First Communion services, rather than staying home making pancakes or going on day trips to fun places or planning elaborate birthday parties at home.

(Birthday parties at home with a bunch of small children—also not a walk in the park, in case you were wondering.)

Even so, First Communion season is a part of my work as a music minister that I really enjoy. The joy, the festivity, the bright shining faces, the pride and teary eyes of the parents—it’s a beautiful thing.

Still…like all of our work and ministry, our shaping of these liturgies will enable them to be stronger and more effective if we are able to step back a little from time to time, try to shed our assumptions, and see what’s really happening. If we remember to peel back the layers of “we’ve always done it this way” and see what of those “always” things are helpful and life-giving, and whether perhaps some of them are in some way hindering the larger vision and mission.

And what is that larger vision and mission?

We are here to form disciples.

I’m going to say that again: Our mission is to form disciples. Our vision must focus on forming disciples.

At least, we hope that’s the vision and mission. If it doesn’t boil down in some way to this, then I’m not sure what we’re about. If we do not keep that in mind, at the forefront of our ministry and catechesis and planning and prayer and music, then we lose the heart of what we are there for.

I would submit that, where First Communion is concerned, we may sometimes lose sight of that mission and vision, perhaps replacing it with one that looks more like “to give the children a special day they will never forget.” Peeling back more layers, we may come to, “to give the children and their families a day they will never forget,” or even “to give the children and their families a day like the one their parents remember, that they will never forget just like their parents remember theirs.”

This is a perilous direction to go in. Not that we don’t want to make this day special and wonderful, and never to be forgotten, for children and adults alike, but that cannot be the core value we hold when we plan and prepare for the liturgies of this day.

For example, let’s look at the process of music selection for liturgies where First Communion is celebrated. Many places where I have ministered and worshiped have the tendency to select for this liturgy music drawn primarily from the school and religious education programs—essentially, music written expressly for small children. It’s an understandable choice, especially from the “make this a special day” perspective, to choose music that speaks expressly to those who are the focus of the day…

Except that the children are not the focus of the First Communion liturgy. Jesus is the focus, the Body of Christ is the focus, the children taking their place at the table is the focus.

Choose music from the parish repertoire, music they will hear on Sunday when they come back to church. Choose music they will connect with the wider community, and with their place in it in the years to come. Choose the music they have sung or heard sung during the Communion procession since they were old enough to hum along with familiar tunes even before they could read, and when the hymnal was too heavy to hold. Choose music their parents can sing with them, music their families visiting from other churches are likely to know as well, so that the sound of the adults’ voices around them can surround them with love and warmth and welcome.

This does not mean, of course, being oblivious in the planning process that this liturgy will have large numbers of children present and taking part, as well as guests and family members who may or may not all be active and practicing Catholics. This would not be a time when I would program “Lord, you give the great commission” or other of the wonderful but wordier strophic hymns that form such a rich part of our musical heritage. I would suggest looking to music with fairly contained tessitura and range, and leaning to more refrain-based songs and hymns. I can tell you that my own kids rarely went around the house during the week singing songs from their catechetical programs, but the regular songs from the Sunday liturgy would be discernable under their breath fairly frequently.

Remember too that this intermingled repertoire can work both ways. If there is a favorite song that has been used at First Communion for many years, even if it may be a little more child-like than the Sunday community would normally sing, consider using it on a few Sundays during the year in the months leading up to the First Communion celebration.

Obviously this whole line of reasoning is heading right back to that topic dearest to my heart, which I espouse over and over again whenever I have the opportunity: Plan your year’s liturgical music early, look at the year as a whole, and know what’s coming up.

It’s all connected.

(Part 2 of this series will look at some specific strategies and repertoire ideas…because no matter how well you plan, getting the assembly at First Communion liturgies can be a challenge…)

Tell the Whole Community of Music Ministers…

(I have posted this every year on Facebook for probably a decade, and I figured, this year I have a blog! So what better place? We all need a little levity, this week of all weeks…)

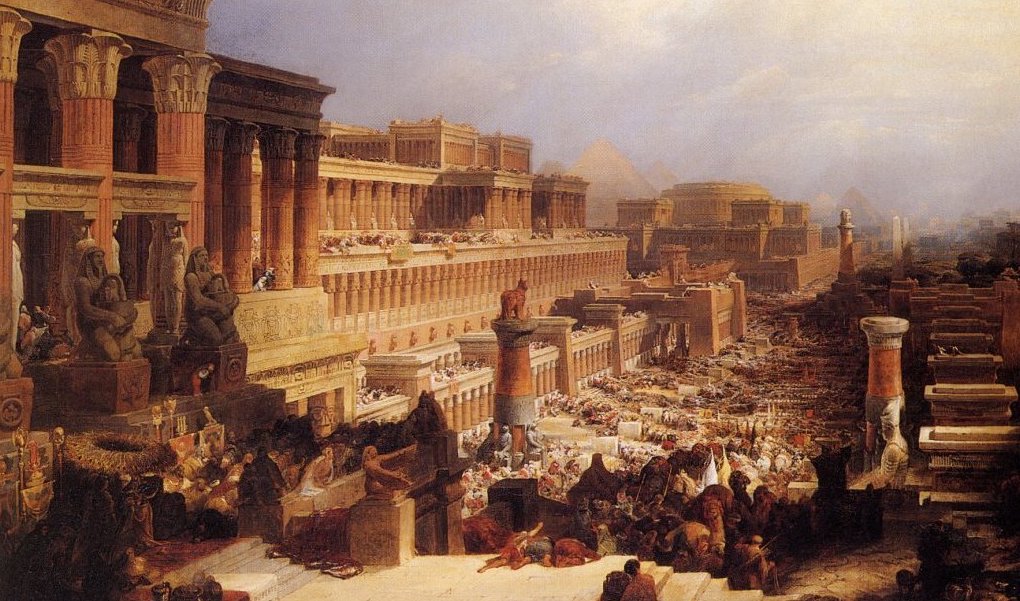

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in the land of Egypt:

Tell the whole community of music ministers: On the night of the Mass of the Lord’s Supper, with no time to cook, you must procure for your family a pizza, one per household unless you eat a lot in which case you might want two. You shall not order pepperoni, lest it give you heartburn during the Mandatum, or garlic, lest it offend your neighbor in ministry.

If a family is too small for a whole pizza, you shall stop at the drive-through for a burger in the evening twilight. This is how you are to eat it: with your vestments or professional blacks on, organ shoes on your feet and your baton in hand; you shall eat like those who are in flight.

It is the Passover of the LORD.

(Peace to all, and blessings for a grace-filled Triduum!)

Night Prayer (Sing Amen! the Podcast: Episode 17)

Podcast: Play in new window

Holy Week is upon us. I figured that at this precise moment in our musical lives no one listening here is looking particularly for new repertoire or deep thoughts or formational development—we are looking to get through the week with beauty and prayerfulness, we are creating folders and scripts and parts for the trumpet players and preparing for a level of intensity that is unlike anything else we do all year.

So instead…here is a calm, lovely Night Prayer service to listen to on your way home from rehearsals this week, or to help quiet down a busy brain after a long day. It’s from Ian Callanan’s collection As Nighttime Falls, a series of 15-20 minute Compline services for each day of the week. These are good for either individual prayer and listening in solitude, or communal or retreat type settings; if you like this, I’d encourage checking out the whole set, available in both audio and music collection form and with an assembly edition as well…

So—all prayers and good wishes to all of us out there this coming week! May you be blessed with choirs who show up on time, cantors who avoid illness, organs that never cipher, string instruments that hold their tune, staff meetings without stress, assemblies with open hearts and joyful spirits, and families who understand when you doze off over Easter dinner. Peace be with you!

Music heard in today’s podcast: from As Nighttime Falls: Hymns, Psalms and Prayers to End the Day, CD-1038 (Sunday Night Prayer)

1 Call to Prayer

2 As Nighttime Falls

3 Be with Me, Lord

4 Word of God

5 Short Responsory

6 Save Us, Lord / Let Your Servant Go / Save Us, Lord

7 Prayer

8 Blessing

9 Hail, Holy Queen

Sing Amen! the Podcast, with Jennifer Kerr Budziak

Sound by Jim Bogdanich

Sing Amen! opening music: Promenade, by Bob Moore (from Let Every Instrument Be Tuned for Praise, CD-491, from Liturgical Suite #4, G-4789 ©GIA Publications, Inc).

Sing Amen! closing music: Amen, (from More Sublime Chant, CD-459, The Cathedral Singers, Richard Proulx, conductor. ©GIA Publications, Inc.)

What’s in Your “Go-Bag”?

Some musicians get to happily stay in one place pretty much all the time, and your home parish is your main place of work. But sometimes you may get asked to play or sing a wedding or funeral somewhere else, down the block or across town. What do you bring?

This question caught me up more than once during my years of full time ministry in one parish, but once I joined the ranks of the traveling subs and “visiting” musicians, I’ve been forced not only to re-think the question but to actually answer it. It’s like packing clothes for an NPM convention; the first couple of times you don’t know what you’re going to need, and then after a while you catch on and it’s second nature. (In case you were wondering, re NPM: At least 2 pairs of really comfy shoes, respectable-but-not-formal layered clothing that lets you not wither in outdoor heat nor shiver in a freezing ballroom, and a good wheeled bag with enough empty space in it to put the inevitable too many books/music you acquire while you’re there. I can do 5 days in a small overnight bag and 1 backpack and still have room for my computer and cables.)

After not very long I stopped asking the question every time I needed to do it, and just gathered what I needed into one bag in the back of my car, so now I don’t even need to check or search or decide; it’s all there. In fact, a lot of regular “musician travelers” I know have something like a “go bag” stashed in the back of their car or coat closet somewhere, packed and ready to go so they don’t need to overthink the process when it’s time to head out to a new place to make music. Here’s what’s in mine (bear in mind that I tend to drive places; if you’re on public transit, you’ll want to slim this down as much as you can):

1. Organ shoes, broken in and comfortable (for women: 1 pair organ shoes, 1 pair clean black flats)

I live in the Chicago area. And often I have to schlep through snow and ice and other grossness to get to my jobs. So knowing I have a pair of organ shoes and a respectable pair of “ordinary” shoes right there in the back of the car at all times has been a life-saver more times than I can count. (And that’s not counting the time I left the house in brown shoes, forgetting that I wouldn’t get back home before a choral concert that evening.)

2. 1 black concert binder, or 1 black concert folder + 1 plain black binder

This is less about music itself than having something respectable looking to hold it in, especially if you are singing. You don’t want to be juggling stuff or God forbid standing up somewhere with a photocopied sheet in your hand. I have a good black concert folder that has three rings in it, which is fantastic; I also have a thin and lightweight concert folder for when I don’t feel like lugging the bigger one around. (I have also had occasion to loan these to cantors or singers who would otherwise have been wandering up to an ambo with a couple of photocopies in their hand.) (Y’all. Don’t be this singer.)

3. my iPad/Hymnal app/ForScore app

Especially if I will be working someplace I know has wireless access, but even if not—this has saved my caboose more than once as well. I can put an entire hymnal of accompaniment onto my iPad, I can download pdfs I’ve legally purchased, and if I’m looking for a classical-type work published before the 20th century, imslp.org probably has it for easy and quick download. (It’s worth paying the annual membership for quick access. And it’s an extremely worthy cause.) While I get a little itchy about only having the electronic option to play from, I now pretty much always bring it. (Er…this one does not live in my go bag in the car, it goes with me into the house.) Chargers and cables too, of course.

4. Before I had a tablet, this next one was on my list, but now not so much: My own personal set of accompaniment books for the denomination I was mostly working at.

In my case, usually this would be Catholic churches or organizations. If you know what specific resource the church you’re going to uses, and you have that, that’s obviously ideal…but those sets get a little pricey, so it’s good to have a set of your own. My primary set is the Gather Third Edition, which has covered most of my bases for years, but I also make sure to own a fairly recent hymnal accompaniment set from the other major publishers as well.

6. What I call my “Survival Binders”

I actually have 3 of these: First, if you don’t already have a binder with the Ave Maria in all 17 keys, the Panis Angelicus in all 12, the Mass of Creation, and a dozen or so of your favorite preludes and postludes (particularly ones that are easy to register on an organ I don’t know very well), I highly recommend your pulling one together. Second, one has my favorite prelude/postlude pieces for solo keyboard, intermixed with versions for keyboard and solo instrument (and the back of it has the solo instrument parts, so I can pull one out for the violinist at a moment’s notice); and the third one has alphabetical dividers and holds all the “one-off” pieces I’ve needed to do for various traveling liturgies.

7. One in Love and Peace (Bob Moore and Kelly Mickus)

This is the dream collection one-stop-shop for traveling wedding musicians, and it has in it pretty much every standard wedding processional or recessional I can think of. Plus each of the pieces it includes are there in arrangements for both piano and organ, with separate available instrumental parts for either C or B-flat instrument. This one’s a keeper.

8. Favorite books and collections I’ve been schlepping around for years or decades

You know, those volumes you’ve had since college with your favorite solo organ/piano works, the stuff you can pull out cold at a second’s notice and don’t even have to find the page because the book just falls open to it. I know I don’t really need these any more, and it would be easier to just put the favorites into a binder or onto my iPad, but I carry them anyway.

So that’s my list at least…I started out with a tote bag for all this, but over the years I’ve transferred into one of those clear portable file boxes with a handle on top. I also keep a zipper tote in the back of my car so I can pull out what I need and not carry the whole thing in with me if it’s not needed.

I asked my friends and colleagues on Facebook what was in their traveling kits, and I got a lot of the same answers—things like tablets, comfy-but-respectable shoes, Ave and Panis in multiple keys, and such came up again and again. As did things like water bottles, cough drops, multiple pencils, or extra pair of reading glasses for those of us who are at that point in our lives. Probably my favorite response had not thought of but definitely will in the future was a small portable battery operated music stand light and extra batteries—I expect most of us have had the experience of finding ourselves someplace where there just isn’t enough lighting, and this would be a handy addition…

Anyone else? What’s in your musician go-bag?

Of Womb and Tomb: a conversation with Kate Williams (Sing Amen! the Podcast: episode 16)

Podcast: Play in new window

Today we have a conversation with Kate Williams, who compiled and edited the beautiful new resource Of Womb and Tomb: Prayer in time of Infertility, Miscarriage, and Stillbirth (G-9816). The resource is made up of a book, a CD, and a music collection, and I’m pretty sure it’s the first collection of its kind—since it came off press not very long ago it has already been adopted by hospital chaplains, parishes, and individuals; it’s been featured on the Music Ministry Mondays podcast for NPM, and Kate will be speaking about it at the Los Angeles Religious Education Conference this week. In today’s podcast we will hear an interview with Kate that we did right after the book came out, interspersed with some readings from the book and some of the music from the collection. (And the prayer we hear Kate read at the opening of the podcast was written by Melissa Carnall, and can be found in the book as well.)

Kate’s work to lift the veil of silence around a pain and grief that we have been culturally conditioned to not speak of, and to shift it out of being a “women’s issue” into a wider concern that affects many many people, both men and women, and to help us find a way as Church to walk through this pain together, and to minister to one another, is tremendously important, and I am so grateful to have had the chance to speak with her about it.

Music heard in today’s podcast:

The Silence and the Sorrow, Liam Lawton (G-5291)

As recorded on Ancient Ways, Future Days (CD-475)

In the Morning, In the Evening, Bex Gaunt (G-9873)

As recorded on Of Womb and Tomb (CD-1061)

And Jesus Said, Tony Alonso (G-7075)

As recorded on Songs from Another Room (CD-648)

SingAmen! the Podcast, with Jennifer Kerr Budziak

Sound by Jim Bogdanich

SingAmen! opening music: Promenade, by Bob Moore (from Let Every Instrument Be Tuned for Praise, CD-491, from Liturgical Suite #4, G-4789.. ©GIA Publications, Inc).

SingAmen! closing music: Amen, (from More Sublime Chant, CD-459, The Cathedral Singers, Richard Proulx, conductor. ©GIA Publications, Inc.)

Joseph Flummerfelt: Gifts from a Master Teacher

I only got to work with Joe Flummerfelt once, for one incredible 45-minute segment of one rehearsal on one ordinary day. He was visiting my teacher, who had been a student of his, at Northwestern University, and Dr. Nally had asked him to conduct a rehearsal of Brahms’ Schicksalslied (“Song of Destiny”) with us.

It was…incredible. I have sung for wonderful conductors before, but this was like nothing else I’d ever experienced. It was like a door somewhere inside him opened, and Brahms just sort of spilled out into the room and flowed all around us, or like he was the painter and we were the canvas and he was just splashing Brahms all over us—like we were not just the artists, but we were also the art itself.

(I also remember, with the part of my mind that stayed calm and rational and in the room, that he sang with us; not the actual vocal parts, but just sort of an under-the-breath vocalization of the sweeping lines he was conducting. It was a little distracting, to be honest—but it also was sort of lovely, and endearing, and it reminded me of Glenn Gould.)

Mostly what I remember was that it felt like magic, like all the mental and rational score study and stick and hand technique we spend our time as conductors focusing on was merely incidental, the box we build to hold the real art, the music and the line and the spirit and the love. And that the important part of what we did as conductors and educators and makers-of-music-with-others didn’t live in that rational world at all. I knew this already, but it was something I’d always felt a little sheepish about, or kept kind of quiet, because it felt like something we weren’t supposed to admit out loud. But here he was—out loud, witnessing it for all of us. I’ve never forgotten it.

Joseph Flummerfelt passed away last Friday night. Somehow this giant in the choral world isn’t as much of a household name among the rest of the musical community in general as I would have thought—like Robert Shaw, for example (who was Maestro Flummerfelt’s teacher), whose name is widely known. But “Flum,” as his students called him, had an amazing history and life. I don’t need to recap his accomplishments—those were not what made him extraordinary. (You can read about them here, though, in this tribute posted by Rider University and Westminster Choir College, or here, in his obituary in the New York Times.) Accomplishments are seldom what make any musician extraordinary. But those rare few whose magic is so great, whose ability to touch something indefinable and essential calls out to the rest of us, are like magnets, pulling us closer. And Joe was one of those magnets. The outpouring of memories from his students and colleagues in these days since we lost him makes that absolutely clear. He touched many lives, and he will continue to do so—that’s what master teachers do; they continue to touch us long after they are gone.

Joseph Flummerfelt passed away last Friday night. Somehow this giant in the choral world isn’t as much of a household name among the rest of the musical community in general as I would have thought—like Robert Shaw, for example (who was Maestro Flummerfelt’s teacher), whose name is widely known. But “Flum,” as his students called him, had an amazing history and life. I don’t need to recap his accomplishments—those were not what made him extraordinary. (You can read about them here, though, in this tribute posted by Rider University and Westminster Choir College, or here, in his obituary in the New York Times.) Accomplishments are seldom what make any musician extraordinary. But those rare few whose magic is so great, whose ability to touch something indefinable and essential calls out to the rest of us, are like magnets, pulling us closer. And Joe was one of those magnets. The outpouring of memories from his students and colleagues in these days since we lost him makes that absolutely clear. He touched many lives, and he will continue to do so—that’s what master teachers do; they continue to touch us long after they are gone.

So why am I posting this here, on a blog that is supposed to be aimed at practical formation for pastoral musicians?

Most of those who know me know that while I have one foot planted firmly in the world of liturgical music and pastoral ministry, the other lives solidly in the arena of choral conducting and art music. This is probably connected to the fact that I tend to view music ministry less as being about directing a small choir singing for an audience of assembly members than about being the person directing the big choir made up of everyone in the room. (Who needs an audience, right?) Maybe I just need the reminder, or want to say out loud, that while the nuts and bolts skills involved in music ministry are of course the key foundation of everything we do, whether as choral musicians or pianists or organists or cantors or whatever our medium of music-making might be, the real movement of the Spirit lies outside of what the skill set can accomplish, and that we as ministers are more than just craftspeople—we are still artists, we are still required to keep our hearts and spirits open and vulnerable and turned outward to the people we serve. Joe Flummerfelt knew this, and he saw his work as the work of holiness; he knew that his work in a concert hall or rehearsal room was no less sacred or worshipful than what happens in any church on Sundays, that the movement of the Spirit is everywhere, whether he phrased it in those terms or not.

Every year at Westminster Choir College, where Professor Flummerfelt conducted and taught for 33 years, one faculty member would give a “charge” to the new graduates at their commencement. A colleague and friend was gracious enough to share his charge to the graduates one year (I believe it is from 1983?) with me. I would like to quote a portion of it here:

“I think one of the great sicknesses of the human condition today is the extent to which we are estranged from ourselves, the extent to which we clamor after gurus of whatever ilk, be they TV preachers, political demagogues, paperback therapists, or the requisite name on the back side of our blue jeans, to tell us who we are, what to believe, what to think, indeed, even to tell us that we exist. Far too many of us look outside ourselves for our center, for our sense of being. And far too many of us are often fooled by the façade or by the label, and believe a thing is what it looks like or what it is called rather than being able to perceive what it is. Lacking connection with our own centers, we lack the capacity to penetrate to the center of that which is about us. Even in our own profession, we are often lured by virtuosity for its own sake, which, though dazzling in appearance, is in fact full of sound and fury and signifies nothing because it springs from no central human or spiritual impulse…Touching center is not an easy thing. But if we believe that it exists, if we believe that the Holy Spirit does dwell within as well as without, if we learn to nurture calm, to be still, so that we can hear the voices within, if we are willing to risk stripping away all of the protective layers with which we have separated ourselves from our core, then the inside and the outside can become one. Then creativity can flow, then the gift of intuition is freed and we are able to see the unity of things, feel the impulse of things…As we grow in love for and acceptance of the life within us, we will become ever more in tune with and resonators for the life about us. We become instruments of the Holy Spirit, and the music we make touches the hearers at their own center and the people with whom we work are helped to connect with the source within themselves. For me that is our calling, as human beings and as musicians. And if we accept that charge, then the glory of God will be ever more manifest in the lives we lead and the music we make.”

–Joseph Flummerfelt

Next blog post I will go back to the more “normal” stuff of liturgical and musical formation. But for this moment, at the beginning of this Lenten season of renewal, this challenge to artists from an artist is one I challenge all of us to carry with us.

Peace be with you, Maestro. Eternal rest grant to him, Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him.

–Jennifer

Header Photo by Carol L. Jenkins

Photo by Steven Ryan

The Mass is Ended, Let’s Sing a Hymn

An interesting question came up last week on the Facebook “NPM Family” group (a lot of interesting questions come up on there—it’s a good place to be!). There was a lot of really thoughtful discussion on the topic, and it’s clear that it’s a topic many of us have grappled with.

The topic: So what’s with the recessional hymn?

Okay, the real original topic was “how do we get people to join in singing the recessional hymn and not leave before it’s over?” but it got far more complicated as we went. Questions like, why try to get people to join in singing it, what is it really, should we even be having one, what is it doing or trying to accomplish when we do, and so forth all broadened the conversation and made things really interesting.

So…what’s with the recessional hymn?

My general M.O. with questions like these is to go first to the documents. I don’t necessarily stay there, and there is a lot of nuance between most lines of most of the wisdom we find in them, but it’s always a really good place to start.

So: the General Instruction on the Roman Missal is very explicit about the role of the entrance song in the Introductory Rites: “When the people are gathered, and as the Priest enters with the Deacon and ministers, the Entrance Chant begins. Its purpose is to open the celebration, foster the unity of those who have been gathered, introduce their thoughts to the mystery of the liturgical time or festivity, and accompany the procession of the Priest and ministers” (GIRM, #47). In the Concluding Rites (#90), however, there is no mention of a song; these rites comprise only the announcements (if necessary) (and may I point out that announcements are intended to go after the Prayer After Communion, not before; I have no idea why so many churches I visit feel the need to put the announcements before the prayer, and then combine the Prayer After Communion with the final blessing…what is that about?), greeting, blessing, dismissal, and the kissing of the altar. No mention of singing or music at all.

However, two articles earlier in #80, we read “When the distribution of Communion is over, if appropriate, the Priest and faithful pray quietly for some time. If desired, a Psalm or other canticle of praise or a hymn may also be sung by the whole congregation.” First, note that there is no provision here for a “meditation” or a choir-only musical selection in this moment. Next, notice that if music is chosen, it is intended to be sung by the “whole congregation,” a song of thanksgiving or praise sung by all. It is clearly optional, but if chosen, it does seem to suggest that the overall function of what we have by tradition over many years adopted as a “recessional hymn” or “closing song” (whatever we call it) is more or less found here—a song of affirmation and praise in response to the celebration we are about to complete. So the concept is there—but the “recessional song,” per se, is not.

Sing to the Lord, the US Bishops’ 2007 document on music in the liturgy, does give acknowledgment to the practice of a song sung by the community at the close of the liturgy. (An earlier document, 1972’s Music in Catholic Worship, alluded to the possibility but was fairly vague about its execution: “A recessional song is optional. The greeting…blessing, dismissal and recessional song or instrumental music ideally form one continuous action which may culminate in the priest’s personal greetings and conversations at the church door,” #49.) This newer document says, “Although it is not necessary to sing a recessional hymn, when it is a custom, all may join in a hymn or song after the dismissal. When a closing song is used, the procession of ministers should be arranged in such a way that it finishes during the final stanza. At times, e.g., if there has been a song after Communion, it may be appropriate to choose an option other than congregational song for the recessional. Other options include a choral or instrumental piece or, particularly during Lent, silence” (#199).

So that’s what the Church and the bishops say. And it’s not a whole lot.

However, in addition to acknowledging the practice of a recessional song, Sing to the Lord offers insight into the question that prompted the Facebook discussion: how to maintain the integrity of a closing hymn as a closing hymn, a communally sung piece of music that completes and ends the liturgical gathering, preferably with the bulk of those liturgically gathered still in the room and taking part: essentially, it says, if you choose this option, it is not intended to be “music for people to leave church by”—it should ideally be structured to end at about the same time the procession of liturgical ministers reaches the back of church. Which is to say, if you have liturgical ministers who bow, turn, and hoof it up the aisle before you’ve completed the introduction of the hymn, it’s probably not going to work so well. (Again, also note that while STTL addresses the possibility of having a choral piece sung at this moment, it also is clear on the distinction between a choral piece and a congregational one.)

Several people on the Facebook post suggested that the musicians speak with the presider, and see if he is willing to stay and sing for a verse or two or at least process really slowly with the ministers, so that the hymn has time to happen, and then finish it fairly expeditiously once he has left. (This is pretty much what I have tried to do, and it is more difficult than it sounds, especially when you have a priest who is not comfortable singing, or standing, any longer than necessary. They don’t always like to do this. Or they think they are standing there much longer than they actually do.) The effect here is twofold: first, getting to sing a couple of verses means the song gets to be experienced as a congregational hymn much the way any other hymn in the liturgy is heard; second, ending it before or just as people are accustomed to being finished and leaving the church avoids letting this congregational piece of music be experienced as “music the choir sings while we do something else,” which is a death knell for the building of an engaged and fully participative assembly. As I said in my own comment on the post, liturgical understanding usually has a lot more to do with nonverbal communication and body language than with anything said in words. So if we say “please join in this recessional hymn” and every week those words serve as a signal for the choir to sing and the people to put down their hymnals and pick up their coats and leave, it not only weakens the singing of this hymn but also the expectation for every time we say “please join in singing” throughout the liturgy– because in this moment at least what we say is not what we all clearly expect to happen. I know many will disagree with me, but in my opinion it’s far preferable to have no “communal” hymn than one that no one but the choir habitually sings, if that makes sense. And it is also important to note that in this model, with the length of the procession dictating the length of the hymn, has direct and often negative impact on the hymn as a complete unit of poetry and art of its own, especially when the poetry progresses through the verses; if we eliminate verses, we risk losing the sense of the hymn and what it is trying to say. So it’s a challenge.

I have also had some success, as a sort of happy (mostly) medium between “just singing enough” of the hymn and singing a complete hymn-poem, with deciding before we begin exactly which verses we will sing and announcing it as such. For example, on the Fourth Sunday in Lent, if we are using the Year A readings as part of our RCIA process with those journeying to the font at Easter, we hear throughout the readings about call, and discipleship, and service, and light, and sight to the blind. For the closing hymn that day, we might say: “As we are sent forth, please join in singing from our blue Gather hymnal, number 764, ‘Lord, whose love in humble service.’ We will sing verses 1 and 3 of #764.” This is a powerful hymn, and the second verse is an important one that I would normally really want to make sure got sung. But if it is for the closing song in liturgy, and if I know that if we tried that, for all practical purposes, most of the congregation would be up and leaving by the time we even started the third verse, which is about light and sight and gaining a vision that stirs us to service for all those we just sang about in the second verse, then I might make the decision to omit verse 2 and be deliberate about the ones I do choose.

This pattern of choosing non-consecutive verses has a happy side effect as well, I notice, especially over time when the verses are well-chosen and relevant to the Sunday. After doing this for a couple of years in a couple of different parishes, I noticed a distinct uptick in people sticking around to the end, even if the procession moved a little more quickly than I hoped–maybe because of relevance, or maybe because when you announce in effect “we are only going to sing 2 verses of this 4 verse hymn, so why not stick around and just finish,” I don’t know. But it seemed to work. And I got good at the happy smile and polite conversation when people would ask questions like, “Wow, that last hymn was right in line with the readings and homily–did you do that on purpose?” I was just happy they noticed!

I was delighted to see a number of people replying to the original Facebook post whose parishes have shifted to the model of a communal song of thanksgiving after Communion, with an instrumental or silent recessional. In this model, the song is itself the expression of praise, a moment for everyone to join in, and the question of whether to remain and be part of it is harder to ignore; the song and the praise become the liturgical moment themselves—a rare thing in a liturgical structure where much of the music is intended to accompany ritual action. Here, the song is the ritual action. I love that parishes are finding success with this, and wish I could transfer it to the churches where I’ve worked. (I’m afraid in most places, whenever I have brought up this possibility at staff or liturgy meetings, I have been met with an aghast, “But…then people wouldn’t be able to leave! They’d have to stay! For the whole song! They would be furious!” And I could never manage to be taken seriously.)

Perhaps my favorite piece of wisdom in the entire thread comes from the ever-wise Diana Macalintal, who I think sums it up beautifully. She asks, “Are people going out to be a sign of Christ to those outside? Are they preaching Christ to all the nations? Are they simply not trying to run each other over as they head for the parking lot exits? Are they seeing the beggar at the church door or street corner as the presence of Christ they are called to adore and serve? If singing a song will help them do that, then sing it. If having the entire assembly sing a hymn of thanksgiving and praise after Communion will make it clear to them the mission they have just said “Amen” to in sharing the Body and Blood of Christ, then do that. If getting them out of there faster communicates the urgency for each of us to go and announce the Gospel of the Lord, then do it! The number of verses sung of the concluding song, even whether or not the people sing it, is less important than whether or not the entire liturgy itself compels them to live the meaning of the liturgy in their daily lives.”

And let the people sing Amen!

So…any thoughts from readers? What happens at your parish?

Why Do We Sing?

By: Diana Kodner Gokce

Explore Sing Amen

Looking for more great resources, articles, podcast, and more throughout all Sing Amen blogs? Search through the site here.

Search By Category

Search Archives