Ministering through Music

Keyboard to Keyboard

¡Cantemos Amén!

Broken and Healed

The Body of Christ in Exile

As wave after wave of news reports on the coronavirus pandemic come crashing down, each more astonishing than the last, it feels like I spend most of my days now in a stupor. Confirmed cases rising, new emergency measures being mandated, and a near-complete shutdown of life seems to be taking hold. Thoughts ranging from the mundane (acquiring groceries and toilet paper) to the uncharted (strategizing the remainder of my children’s school year spent at home) to the worrisome (the health and safety of family members separated by long distances) all collide at once, impossible to sort out but incessantly driving up adrenaline levels. While the initial shock may have passed, there remains a numbness, a sort of defense mechanism, against the onslaught of uncertainty. Hunkering down and sheltering in place, we ride out the storm with a mix of disbelief that something like this could actually happen, and the pain that the simply unimaginable is now so real.

Disbelief at the Unimaginable

Everywhere I look, stories abound of people thrust into a juggling act of new, converging work and family realities. For those of us lucky enough to be in a situation to do so, it’s not just a question of doing work from home but of trying to maintain some semblance of family balance, productivity, schedule, and yes, purpose.

Simultaneously, so many are truly suffering. While small comfort can be found in that fact that “we’re all in this together,” there’s no denying that many are especially vulnerable and taking a huge hit. You don’t have to look far to find friends, colleagues and loved ones around us really struggling with the financial and health toll.

For El Pasoans, there are not-too-distant echoes of another unthinkable event suffered locally. The racially-motivated shooting that occurred at a Walmart store on August 3, 2019 was a day of tragedy and sadness that forever changed life in this region. Not unlike September 11, 2001, it unfolded in waves of uncertainty. As we did on those occasions, in recent weeks we’ve all stood glued to the news in disbelief of each new development as we witness this pandemic’s devastation in real time, collectively absorbing the shock, anger, and desperation at all that is taking place, bracing for its immediate and far-reaching impacts. Like those August and September dates, life after this coronavirus will never be the same.

Desperate measures for desperate times

In our own communities, parishes in particular, are bound to feel the hurt on many levels.

In places where masses have been suspended, the first emergency action for many communities has been setting up a means to facilitate virtual worship. Parishes and dioceses in all corners of the country are coming up with methods to broadcast their masses online. It’s been wonderful (if a little overwhelming) to see parish after parish show up in my newsfeed with info or links to their live broadcasts. In this regard, technology has been a tremendous tool in alleviating the separative effects of this pandemic that even ten years ago was not imaginable, a kind of manna in the desert to keep us sustained until we can once again partake of the true banquet.

Still, as many have noted, watching mass is not the same as “being there” in person. Passive observance at home doesn’t feel the same as actively participating in the pew alongside others who form the assembly of faithful, joyfully fulfilling their right and duty to praise God in the sanctuary of his holy dwelling.

So much could be said of this irony—theologians can certainly break this open with much greater wisdom—but we are living a time in which the broken body of Christ remains in triage, unable to come together in person for much-needed prayer, for much-needed healing.

Hanging up our harps

Though we don’t hear the biblical story until next year’s cycle of readings, there’s certainly parallels to be found these days in the Babylonian exile. The Jewish people did not know how long their captivity would last. They knew only that they must persevere, even if it seemed that all hope was lost. Imagine the first few years, the captives holding on to a glimmer of hope that they could return home in their lifetime, and that glimmer slowly flickering out as the years turned to decades, then to generations. How did they survive the utter despair?

They asked themselves, “How can we sing a song in a foreign land?” As if to say, “What’s the use? It’s better for us to hang up our harps and call it a day!” For us these days, isolated from our parishes, our exclamation might be, “How can we sing our song in a liturgically foreign land?” As the world is reeling from COVID-19, our church, too, is suffering its affliction, the members of its body in exile from the ability to worship together in community.

The captor in our case is not an enemy people, but a tiny micro-organism—a virus holds us captive (!). But perhaps we were held captive already by our own entrenchment in a secular world, the inability to break free from the overload of non-essential things, the inability to become unglued from our phones, tied to social media and the facade it provides for toxic spewing of hatred and disrespect. The growing contempt we routinely harbor for those who are different from us politically, religiously, in sexual orientation, gender identity, or legal status… Are we not all the body of Christ, sisters and brothers to each other with one Father in heaven? We mire ourselves in tending to these life-draining behaviors and attitudes, when our energies toward what is truly life-giving—love for God and one another, discipleship, and our call to spread this word—all but vanish. For all its scourge on humanity, this pandemic is a reminder of our inter-connectedness. Imagine if only it were the Gospel being spread as infectiously as this virus.

40 days in the desert

The liturgical context in which this pandemic is happening cannot go unnoticed. Every year we traverse the Lenten season as we prepare for Easter, but somehow these recent events have amplified the treachery of this particular stretch of ritual terrain. Being sequestered in this imprisoning desert will cause many to ponder this year’s Lenten journey in a deeper, more profound way. The hunger for meaningful connection will be felt by us all, as will literal hunger be felt by the economically exposed. Lent rolled around this time not just as an inconvenient period of no-meat-Fridays, but a dire new reality of real human suffering.

Here in the borderland between the U.S. and Mexico, the notion of the Gospels’ desert is not some disconnected, far-off narrative, but a daily lived reality. In the absence of shelter, the high-desert climate here in the Southwest can be surprisingly harsh: scorching days and frigid nights. The lack of rainfall, the huge expanses of barren land, mountainous backdrop, rolling dust storms, and flash-flooding thunderstorms, all paint an ever-present picture of a stark, albeit it wondrous, landscape. It reminds us of Christ’s humanity—the hunger he surely felt during his fast or his own childhood exile into Egypt (and the fear his refugee parents must have known on that journey). In this region where two nations meet, a line in the sand defines boundaries that force family separation, and the desert forms the unforgiving life-or-death stage for those who dare cross it. Here along its barren miles, the migrant or refugee approaching the altar of a more dignified life is met only by a brutal steel barrier.

Yet in spite of these obstacles—whether the realities that existed before this pandemic (and will continue to do so) or the calamity of this viral invader—we carry on, bearing the crosses of isolation, job loss, financial uncertainty, sickness, suffering, or death of loved ones in this crisis. Despite the crushing weight and burdens that at times seem too much to carry, we heed Christ’s call to follow him on that arduous way. Why? Because the story doesn’t end at Calvary but with the stone rolled back from the empty tomb.

Return to God with all your heart

Before entering the gates of Jerusalem, Jesus went into the desert to pray and fast. He went into that barren wilderness not because he was forced to, but because it provided the very setting needed for his own preparation. It was his intentional social distancing, his retreat from the daily path in order to remain focused on the wondrous events to come. Over 40 days, his body hungered so that his spirit could be fed.

Perhaps this exile of ours from the communal celebration of Misa is a chance to reestablish prayer more meaningfully in the home: prayer alongside daily chores, routines, Netflix®, and smartphone addictions. The desert exile gives us the opportunity to reflect, prepare, and change. Through our fast we can more clearly see where we have gone astray and prepare our hearts for a return home.

Bread broken for the world

Just as God sent manna in the desert to tide over the hunger felt by his people wandering the desert, we have the temporary nourishment of virtual celebrations of Misa. It’s not the true substance, but it sustains for the time being. And it sustains a sense of the connected, albeit fractured, Body of Christ.

But it’s important to remember that bodies get broken. And they heal. Christ’s own body was brutally scourged and tortured over the course of his Passion, but out of this suffering came the Resurrection which restored and glorified his body. Jesus took bread and broke it, giving it to his disciples to share and consume. In receiving his broken Body we thus become his Body, healed and healing for a world in its need. Through him, with him, and in him, we are promised restoration, and like those emerging from the desert exile, a reclaiming of what was lost so that we may joyfully proclaim what is to come.

Thus our Lenten fast becomes infected with Advent hope, and we now await a reuniting—and re-igniting—of our faith communities in the wake of this viral scourge. Our longing has been foreshadowed in the psalms: “My soul thirsts for God, the living God. When can I enter and see the face of God?” (Ps 42:3). It is with joyful expectation that we await the day when we can once again “pay our vows to the Lord in the presence of all his people” (Ps 116:18) and gather as the Body of Christ, in all its beautiful brokenness.

Let us sing Amen. Cantemos Amén.

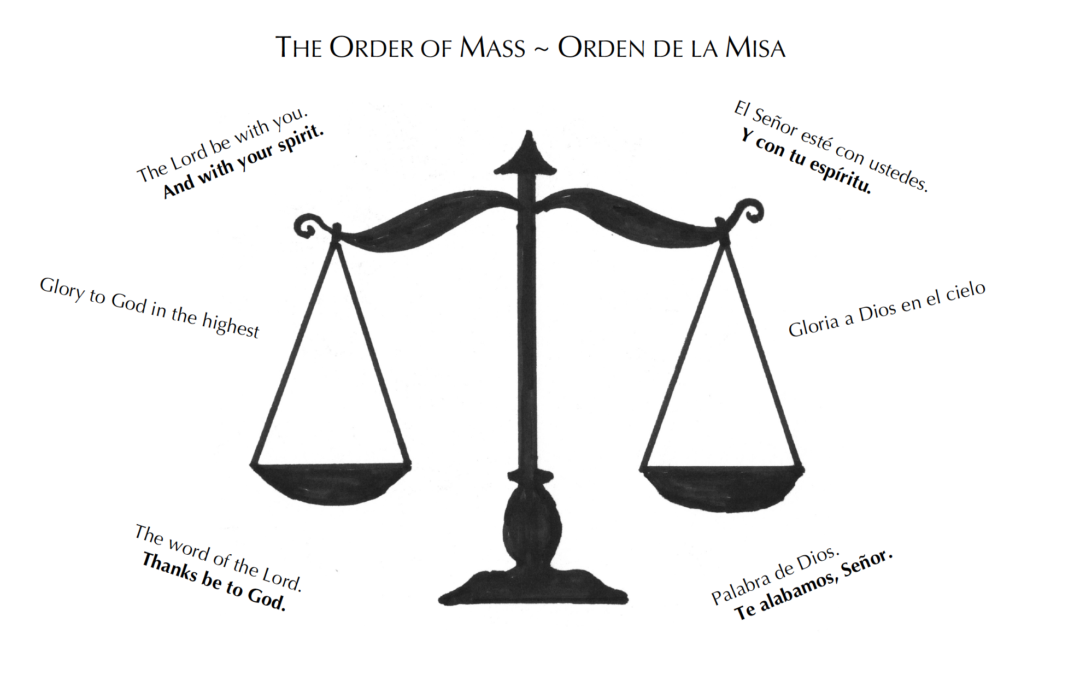

A + B = C: Bilingual Homilies

A Look at the Challenges and Mechanics of Effective Bilingual Preaching

When it comes to delivery of spoken text, whether proclamation of the Word, the homily, or even the Sunday announcements, how these moments are treated shapes the overall experience of prayer and welcome for the community gathered. Because it’s the part of the mass that is ritually unscripted —and typically of some substantial duration—, we’ll talk here about the homily.

The Wholesale Approach

In a bilingual mass, there’s a few schools of thought as to how best to deliver a homily in different languages. One frequently-used approach is for the homilist to deliver their homily first in one language completely, then the other — the thinking being that in order for “each side” to get a “full share” of the preaching, the whole thing needs to be repeated in both idioms. There are merits to this approach, as it guarantees a dutiful, meticulous delivery of content. Yet as a listener, I’m often disenchanted by the tediousness of “doing it twice.” The repetition of an already-elongated component of the liturgy is often a detracting factor from even stellar content. While functional, I’m hesitant to call the approach enjoyable. Granted, I’m a bilingual listener, so to hear the homilist’s entire message again can feel like a bit like deja vu (cue collective eye roll and sigh as one language finishes and the whole homily is queued up again in the other language). Additionally, when unfolded in real time, there’s an unavoidable span of time wherein the single-language listener cannot help but feel excluded and disengaged from the homilist. Couple that with the element of “who gets their turn first” in each period of “linguistic recognition” while the other side waits it out — another reason why I’m not completely satisfied with this method. That being said, for monolingual listeners the “repeat in the other language” model can be admittedly helpful and appreciated.

Taking into account the pastoral wisdom of the moment and setting, along with the homilist’s own linguistic comfort level, if indeed the wholesale repeating of texts in one language then the other is the most apt solution, its effectiveness can have much to do with the delivery. Lest the homily become unduly drawn out and disconnected from large swaths of the assembly, the homilist should take care to be clear, engaging, and expedient in delivering the text.

“Story at 11”

Perhaps a useful study can be found in the news industry. Newscasters inherently pride themselves on efficiency and clarity in delivery, with ratings and careers hyper-dependent on such factors. In the news business, delivery is crucial because of the timed nature of each segment of a broadcast, and the speaker is expected to deliver their script within the prescribed time.

I live in the border city of El Paso, Texas, where it’s common —even expected— for local news reporters to be bilingual. As such, many of these journalists are adept at interviewing a person in Spanish and English simultaneously. Their questions might be stated in both languages, for the benefit of the responder and the viewer, but it’s always delivered quickly and succinctly so that there is not disproportionate emphasis on the interviewer. If you’ve ever seen someone like Jorge Ramos from Univision or journalist Mariana Atencio dialoging with an interviewee bilingually, you’ll get the idea of how speed and clarity make a difference. In finding a parallel with a bilingual homily, it’s not a far stretch to understand the importance of these very factors.

This brings to mind, most curiously, the bonus material on the DVD for Mel Brook’s comedic movie, “Young Frankenstein” (weird connection, I know!). One of the bonus features is a segment where the main actor Gene Wilder and his co-stars are interviewed —in English and Spanish (!)— by a Mexican reporter who is quite skilled at bilingual delivery. While I cannot figure out the Spanish-language connection to the 1977 film’s promo agenda, it impressed me that this interviewer was so adept at a smooth bilingual delivery that the actors could respond naturally and remain unphased by what could have become a linguistic (and mental) barrier. (Given the comedic nature of the film, they even have a bit of fun with the language angle.)

All this to say, when delivering a “repeated” text, if the homilist is efficient, engaged and animated, even the non-understanding listener can at least feel “drawn in” to the spirit of the message until their own language is heard. And for all my apparent critique of wholesale repetition, there is something to be said, curiously enough, for repetition in musical forms; after all, litanies are built upon this very premise. Repetition can pave the way for “steeping” our souls in a particular message (think, in particular, of the mantras and ostinato refrains employed in the Taizé tradition and just how powerful a means to prayer they are). So, in spite of petulance on the part of this listener for having to endure a double dose of preaching, I readily acknowledge what a privilege it can be to hear “twice” God’s Word broken open. It’s not unlike wanting to see a good movie again while it’s still in the theater!

Intertwined Approach

Now a different approach to bilingual preaching might be for the homilist to weave together shorter portions or narratives that keep the listener engaged, even in periods of non-comprehension, through more frequent linguistic “installments.” These portions don’t necessarily have to be verbatim repetitions of each other, but rather threads that keep the momentum moving. For example, in a bilingual English-Spanish homily, the various fragments or portions in English amount to a thread of its own, while what is said in Spanish also constitutes its own mini-thread; and together, the aggregate of both “threads” comprise a cohesive homily. Formulaically, this interwoven technique might look like this: A + B = C, whereby A and B are each stand-alone narratives in opposing languages, and the sum C is the full result of the two intertwined. With either A or B both yielding a cohesive and satisfying result, I note the wording used by the Church in regards to the “total presence of the Lord Jesus Christ whether … under one form or … both kinds” (in reference, of course, to reception of holy communion under both species) as an interesting analogy here in the breaking open of his holy Word via different languages.

This “toggling” between languages is indeed a developed skill, because it involves language facility and story-telling creativity. Persons who are naturally bilingual can often hone this craft, taking this method of bilingual homiletics to great heights. I think specifically of Bishop Emeritus Ricardo Ramirez of Las Cruces, who in each of his homilies, takes the listener on an enthralling spiritual journey as his narratives unfold in either language. The languages are mixed so naturally and seamlessly that the listener can forget that they don’t understand all of what’s being said, but is fed enough of a preached meal that they feel satisfied by the end, as if having indulged in a banquet.

In Conclusion

There are other approaches beyond those explored here, including more adventuresome ones involving audio and visual technology, simultaneous interpretation, projected texts, or printed medium like prepared bulletins or worship aids. When formulated and executed with the listener in mind, these all have potential to effectively convey the homilist’s content across multiple languages.

It’s important to stress that as a member of the laity, I am not a homilist; these observations are purely from the pew perspective and admittedly and comfortably removed from the stresses and pressures homilists undoubtedly face each time they prepare to preach, in one language let alone two. Nevertheless, I do find myself in a fair share of situations where I must speak to an audience bilingually. I know well the immense challenges posed by such scenarios —from timing to effective conveyance of content—, but also recognize and cherish the incredible gift of a “Pentecost moment” to address the gathered Body of Christ. Those of us entrusted with pastoral speaking are in a unique position to transform, regardless of language, through each encounter.

Secondly, to my ordained friends reading this, I don’t mean to oversimplify or otherwise presume my suggestions constitute some kind of instant formula for cultural success or magical solution to the difficulties of bilingual preaching. I commend your commitment to the ever-constant call to break open the Word of God for us, the faithful, in relevant and meaningful ways while simultaneously addressing multiple cultures. As your listener, I thank you and continue to learn from your collective efforts in this new linguistic reality.

We’ll explore other moments of the mass and their texts in future posts. For now I hope you’ve enjoyed giving some thought to (and discovered a newfound appreciation for) the mechanics behind bilingual preaching, whether from behind the ambo or in the pew.

¡Que cantemos amén! Let the church sing Amen!

Cover image: Fr. Michael Lewis of the Diocese of El Paso preaches at Mundelein Seminary. Photo courtesy of Mundelein Seminary, usml.edu

Healing for a Wounded Community

Today marks three weeks since the mass shooting in El Paso, TX, where twenty-two innocent lives were taken at a Walmart store and dozens more wounded.

In the days since the shooting, prayer vigils, gatherings, rallies, events, fundraisers, and, most importantly, funerals have all taken place as the dead have now been laid to rest. Victims’ families continue to mourn their losses, and the entire city simultaneously grapples with a commitment to remember and a will to move on.

The community’s wounds are still fresh, but there’s a sense that we need to carry on with our lives, lest we fall victim to the perpetrator’s intent to instill fear and fundamentally alter that basic tenant of humanity. No, that will not be the case. Life will go on. And love will go on. As heard many times in Gospel proclamations, homilies, and speeches, it is love and only love that can overcome such hatred. Defiant, intentional love in the face of evil. In love, we encounter God’s grace to lead us through this dark valley.

A new bond now permeates life here in El Paso, even if never spoken or overtly acknowledged: In being collectively violated and made vulnerable through this person’s act of hate, there has also been a universal exposing our true selves, the inner self in all of us that simply wants peace and harmony. All other pretense has been stripped away. The “what if” factor each of us feels has forced us to come to grips with what really matters. (My new mantra: “Hug those closest to you profoundly and profusely”!) And as if this community weren’t already close enough by virtue of its familial underpinning, this vulnerability has just further cemented a spirit of kinship among complete strangers. It’s like the Body of Christ is actually recognizable out on the streets!

The open wounds start to heal, at least a little. The community is returning to regular life, and there’s moments when all seems “back to normal” — those undefined, mundane, semi-hazed flashes —walking in a parking lot, shopping for groceries, unloading a shopping cart— where the routine and rote-playing of daily motions are as if nothing remarkable had ever taken place here. But then the memory hits. The brain resets and you instantly bring it all back into focus. Something is different and will always be different going forward. The road to healing will be a long and winding one, for sure.

As life sputters and struggles to return to a sense of normalcy for the majority of us in El Paso, lingering concern remains for the forty-six families who were thrust into the middle of this tragedy because of complete happenstance the morning of August 3: twenty-two families who’ve had to bury loved ones, stripped of their earthly lives in a blazing instant at the hands of hatred and fear; another twenty-four families whose loved ones are forced to cope with the permanent effects of bullets that pierced their bodies.

Prayer Transcending Borders and Time

Particularly heartbreaking is the fact that twenty-two funerals have since taken place. The aftermath and its liturgical implications were extraordinary. In just ten days, all victims were laid to rest in masses or services held in El Paso and in Ciudad Juarez. Recall that several of the victims were from Mexico, their bodies returned to their families in Mexico for burial there. One of the “Mexicans” was actually a German native, retired from the German Air Force after serving at Fort Bliss U.S. Army Base and residing in Juarez with his Mexican wife. In virtually every case, families of the victims spanned either side of the border, and certainly the community’s outpouring from either side was not impeded by any wall or physical barrier.

Because of the number of funerals held all within a relatively short span and in different locations around the region, the individual liturgies formed part of an aggregate communal prayer. In the same way the Paschal Triduum constitutes a single liturgy across three days, these funerals were like a unified, multi-part celebration commending these twenty-two souls to heaven. It was an extended litany of new life, with precisely twenty-two invocations. At any given funeral mass, there was a sense of something more than just the liturgy at hand — you were actually taking part in a days-long, multi-movement symphony of redemption and reception into paradise.

“Ministerial First Responders”

In all, I assisted with five of the funeral masses, planning, playing and leading the music. Like many El Pasoans, I had been wanting to make a meaningful contribution to honor the lives of the victims and somehow assist the surviving families. I invited members of my diocesan choir to join me in this effort. I was overwhelmed by the impassioned and immediate response by so many. Choir members dropped everything to be part of not one, but four(!) different liturgies in one week — all at different locations and some even back-to-back on the same day.

Together, we became “ministerial first-responders” to the tragedy, assisting in the best way we knew how: through our ministry of music, liturgy and sung prayer. Though a miniscule contribution in the scheme of things, this was our way of applying a spiritual triage, treating the immediate needs of the suffering, tending to their earthly souls while at the same time commending the souls of the deceased to the divine. What a humbling privilege.

And, as it turns out, in giving of ourselves, it was also a way to tend to our own self-healing. God’s grace is indeed found in all things.

Victims’ Masses

On Friday, August 9, we sang for Angelina “Angie” Englisbee, age 86, whose funeral was held at St. Pius X church. It was an uplifting celebration of Angie’s life. Family, friends, parishioners and city leaders packed the church, and along with the full choir and instruments sang her from this earth to heaven’s gates.

That same day was the funeral mass of Juan de Dios Velazquez, age 77, a naturalized U.S. citizen who had moved to El Paso to escape the violence of Juarez. It was a smaller, more intimate service, held at Our Lady of the Light church, a small parish in what’s known as the lower valley, close to the U.S.-Mexico border. There was a palpable grief among all those in the pews. Juan’s surviving wife, Nicolasa, also wounded in the attack, attended the funeral in a wheelchair, assisted by medical personnel and transported by ambulance. After the mass, which was entirely in Spanish, the pastor expressed his gratitude that we were there, because otherwise there would have been no music.

The following day, Saturday, August 10, the one-week anniversary of the massacre, our community laid to rest 15-year-old Javier Rodriguez, the youngest of the 22 killed. The bilingual funeral liturgy took place in the early morning at Corpus Christi church, which was filled to capacity. Going into this mass, we all had a sense that this would be a particularly emotional ordeal because of the age of the victim. Javier’s uncle, who was with him at the time of the shooting and himself was seriously wounded, was transported from the hospital to attend. During the mass, my daughter Chloe sang a solo reflection piece, “Deseo paz,” a plea for peace and end to senseless violence. It was a moving moment for all. Upon procession of Javier’s casket out of the church, the entire crowd waved white cloths above their heads in farewell to this beloved child of God.

On Wednesday, August 14, I played at the Spanish-language funeral mass for Gloria Irma Marquez, age 61, of Ciudad Juarez. Her mass was held at St. Patrick Cathedral, attended heavily by family and friends from across the border, many of whom wore white in Gloria’s honor. I assisted the small cathedral Spanish choir on organ and piano and together we led well-known songs in Spanish to which all raised their voices. I was struck by the simple serenity that permeated the entire celebration.

On Friday, August 16, the full diocesan choir sang for the funeral mass of 23-year-old Andre Anchondo, the young father who was killed, along with his wife Jordan, in the massacre. The recently married couple died protecting their two-month old son. A lot of media attention surrounded this particular story because of the heroics involved, the young age of the victims (both in their 20s), and the plight of their three children left behind. Bishop Mark Seitz presided the mass, offering a moving homily that comforted the grieving assembly and reminded all of Andre’s propensity for fun, laughter, and for “doing things big.” The choir, organ and trumpet led glorious music that lifted saddened hearts, compelling all to rise above our own grief so that we could in turn lift up Andre. “And I will raise you up, and I will raise you up on the last day” were the resounding words from Suzanne Toolan’s ever-timely hymn echoed by all.

Life Remembered, Life to Live

The week after the tragedy, I took my daughters to see the victims’ memorial at the Cielo Vista Walmart where the shooting took place. In the weeks since the shooting, a makeshift shrine has grown organically into a beautiful, sprawling wall of crosses, flowers, candles, hand-written messages, photos, crafts and artwork to form a kind of urban coral reef, expanding each day in tribute to the victims. It is truly a sight to behold, simultaneously a communal proclamation of unity and outpouring of care from within and abroad. Even amidst the hundreds of daily visitors and driveways and streets around the area now being reopened to traffic, the atmosphere at the site remains solemn. Complete strangers hug and console each other in what becomes a more distant, yet ever-present grief.

That day, standing before the twenty-two crosses, we said a prayer as a family for the victims.

And then, with sad but grateful hearts, and reminded that life must go on, we went shopping at our regular Walmart.

And so is it that we as the Body of Christ remember and honor those members who have been called to eternal life, just as we continue to live ours in joyful pursuit of the same heavenly reward.

#ElPasoStrong

Let the church sing Amen! ¡Que cantemos Amén!

Praying for El Paso

This past weekend, 22 people were murdered and dozens more seriously injured in a mass shooting that took place in El Paso, TX, the city where I live with my family and call home. The shooter was a lone gunman who traveled more than 600 miles to target and kill Hispanics in our city for fear of a “Hispanic invasion” of our country. The massacre took place at a local Walmart store on a Saturday morning, while people were buying groceries and families shopped for back-to-school supplies.

The shooter came from a Dallas suburb to do this evil deed, after having posted a hate-filled manifesto to his social media. The community was violated. Brutally, horribly violated in the worst possible way. A 15-year old high school sophomore, a young mother, her husband, a grandfather, a grandmother, and numerous others all with beautiful lives to live and loving families, all mowed down in an instant with bullets and a machine gun. While most of the victims were U.S. citizens, eight of them were actually Mexican citizens, not even from this country. They were not invading; they were going to go back home, to their own country, after shopping. This man wanted these people —who he did not know and who were not like him— to suffer, to pay the price of his anger and hatred, not knowing that they would have probably taken him in with profound kindness and compassion. That is the sad irony.

Border Reality

The community of El Paso is unique. It shares a border along the Rio Grande with the city of Ciudad Juárez in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. It is a peaceful, loving community. I can best describe the environment as insanely hospitable. Really! People routinely greet each other with kind, cordial (and actual!) dialogue: “Buen día, ¿cómo está?” or “Hola, ¿qué tal?” or “Con permiso, por favor, muy amable.” Children are regularly addressed as “mijo” and “mija” (“my son” and “my daughter”) by kind, though unrelated adults as an expression of care. There is a sense that if you were ever stranded and needed to knock on someone’s door for help, not only would you get that help, you’d probably get a fresh, hot, delicious meal and a place to stay for the night. This is a city of hospitality, warmth, and welcome, infused with a sense of family and neighborly love.

It’s especially hard for others in the U.S. to comprehend just what a safe place this border city is. You might ask, how can a city that shares its municipal and international boundary with one of the most notorious cities on earth, Ciudad Juárez, be so secure, when its neighbor is literally ravaged in crime and lawlessness? That’s the paradox, así es. To quote Bruce Hornsby, that’s just the way it is… in a good way. The violence to the South doesn’t spread across the border. El Paso reaps the benefits of a population that cherishes its peace and safety. The drug-driven activity of Ciudad Juarez remains over there or is transported to other U.S. cities with drug epidemics, bypassing El Paso, which is left largely untouched by these elements.

So much of the general population of El Paso is Hispanic, the great majority of Mexican descent. Spanish and Spanglish are primary languages alongside English for much of the population. Families share their lives on either side of the border. Tías, primos, abuelos, even padres may live on one side while children and other family members live on the other. They come and go from both sides, peacefully and as part of the daily way of life. They visit each other and celebrate cumpleaños, bautizos, bodas, or holidays as family. The economies are intertwined. Many El Pasoans —U.S. citizens—, make the daily commute to Ciudad Juárez to work in the sprawling auto supply manufacturing industry there; these are white-collar workers with engineering degrees. Likewise, many bright, talented young people from Mexico make the daily commute to the U.S. to attend the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). They pay their tuition like anyone else, enrolled as international students in this iconic institution of higher education. Afterward, they all return to their homes, whether on the U.S. or Mexican side, sometimes spending several hours in line to cross the 1/4-mile long, international bridge. That’s life here. And it is beautiful. And peaceful. And safe.

And upsetting to those who fear difference.

The particular store targeted by the shooter in El Paso was one that is but a few miles from the Mexican border. Mexican residents routinely shop at this Walmart because the selection of goods is greater and prices actually more affordable than what they can find in their own town. (Something you and I take for granted as we zip to the neighborhood market or superstore just minutes from our homes.) It’s worth the time and effort for them to go on an international journey just to do some routine shopping for household goods, clothes, and school supplies.

Turning to Prayer

In the wake of the tragedy, prayer vigils and rallies were scheduled. Memorials and funds were set up. Immediately, the city and community came together to grieve, find strength and solace, vent anger, and pray.

I provided the music at one impromptu diocesan-wide prayer service, hastily scheduled in the wake of the tragedy that same evening. I figured that plans were probably still up in the air with details. Sure enough, with such short notice and general city-wide chaos, the planners had not had a chance to think much beyond a time and location, so I came prepared to step in and ensure that music was part of whatever prayer took shape. I’m not even sure why I showed up, because all motions that day felt numbed; I only I knew that I needed to be at church in prayer with my community of faith and that we needed to sing.

Announced to begin at 7 pm, just 8 hours after the initial 911 calls were made, the community filed in that evening to St. Pius X church, quietly and still stunned. The beautiful church, where my wife and I were married, sits along the I-10 freeway, less than a mile from where the shootings took place. Fr. Michael Lewis, a native of El Paso and recently ordained, led a beautiful bilingual liturgy that both comforted and united all present through God’s Spirit and Word. We listened to readings, prayed our petitions, mustered strength to sing our grief, carried forth 20 candles for the deceased, and prayed a litany to the sacred heart of Jesus. The Gospel reading was from John 14: “Do not let your hearts be troubled, have faith [for] I am the way, the truth, and the life.” Media cameras clicked incessantly all throughout.

Fr. Mike’s preaching was impassioned, compelling, honest and raw. The disbelief and horror of the moment were still fresh on everyone’s mind. At one point he confessed to us all, “I’m barely holding it together here,” stating that afterward he was headed to the hospital to anoint the wounded survivors of the attack, some of whom might not survive. (Sure enough, two more victims were later added to the initial count of 20 deaths.) Yet, the principal message was one of love. Defiant love. Illogical, incredulous, unwithheld love in the face of hatred. Because God’s love will always overcome evil and violence, love was the key to unlocking our own comfort and healing. Powerful words. Tough message. Gospel truth.

Liturgy in Tragic Times

While strange to think of or somehow be focused on liturgy in the face of such unspeakable horror, I couldn’t help but be moved by the sight of this gathered assembly at the prayer service. It truly was the wounded, suffering body of Christ. As I entoned the opening strains of the hymn “You Are Mine” by composer David Haas, with its refrain that says “Do not be afraid, I am with you,” I heard the people singing. Emphatically, defiantly, gloriously singing. We were singing our sorrow, exasperation, confusion, and surrender that day. But we were also singing our faith, trust, gratitude and determination. As the document Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship reminds us, “Our participation in the liturgy is challenging. Sometimes, our voices do not correspond to the convictions of our hearts. Other times, we are … preoccupied by the [troubles] of the world” [Sing to the Lord, 14]. But it is Christ himself, whose body was brutally wounded and weakened, who invites us —each of us, personally— “to enter into song, to rise above our own preoccupations, and to give our entire selves to the hymn of his Paschal Sacrifice for the honor and glory” of our triune God.

From my vantage point as the lone musician, I looked out on the faces of the assembly. Further contemplating the sad events of the day. I recalled the section from Sing to the Lord which states, “Because the gathered liturgical assembly forms one body, each of its members must shun ‘any appearance of individualism or division, keeping before their eyes that they have only one Father in heaven and accordingly are all brothers and sisters to each other’” [GIRM, 95, as quoted in STL, 35]. That rogue thought led directly to this next one: “Why, O God, could not these words have fallen onto the ears and into the hardened heart of this evil shooter? Could not, even for him, a change of heart have taken place if only love had been given a place to take hold?” My head hung in defeat.

But then I looked at what was before me. People from all around the city were gathered in prayer. No matter our individual race, culture, language, or other external difference — we were and will continue to be brothers and sisters to each other with one Father in heaven. In this truth was revealed God’s grace. Amidst the profound sadness, a small but knowing smile formed.

To close the service, I led the well-known song in Spanish based on psalm 116, “Caminaré en presencia del Señor.” People sang with fervor, wanting their voice heard. With its verses that speak of anguish, sorrow, and falling into the snares of death, the refrain rang forth each time professing that we, together as the beautiful, multicultural and ever-hospitable community of El Paso, will indeed choose to walk in the presence of the Lord, in the land of the living.

And our light will shine forth in the darkness.

For we are #ElPasoStrong.

Let the church sing Amen! ¡Que cantemos Amén!

If you would like to give to the victims’ fund: please visit:

https://pdnfoundation.org/give-to-a-fund/el-paso-victims-relief-fund

If you would like to give to Annunciation House, which shows El Paso’s ongoing hospitality through its care and welcome for refugees and migrants:

https://annunciationhouse.org/financial-donations/

50-50… What Makes a Liturgy Bilingual?

Welcome back! Bienvenidos de nuevo a ¡Cantemos Amén!

I saw a post awhile back on a pastoral musicians’ forum that caught my eye. Music directors were responding to a question posed by a colleague about how much English versus Spanish there should be in a bilingual liturgy. Several responded, rather matter-of-factly, that the obvious answer is that it should be “50-50” — that is, equal parts English and Spanish. This got me thinking…

What makes a liturgy bilingual?

I’ve attended, prepared, or ministered at dozens, possibly hundreds of bilingual liturgies over the years, including outside of eucharist. One thing that struck me was that the most successful and memorable celebrations, at least in my mind, were not necessarily “equal parts” Spanish and English. In fact, they didn’t even carry with them a sense of quantitative measure or ratio, but simply “felt” right.

Perhaps this aspiration toward balance should be a question of “what does it feel like in prayer” more so than “what does it look like on paper.”

From my perspective both as a pew prayer-er and as a liturgy preparer, a bilingual mass cannot be measured in terms of percentage or quantity of texts at play, nor should it. Merely “dividing up” the liturgy to meet an arbitrary benchmark demotes the ritual to the level of a commodity, like something to be parceled off or “distributed” at the discretion of those who wield such power (the image of casting lots comes to mind). To put an artificial quantifier on the “degree of bilingualness” as the desired measure in itself misses the point. I would caution against framing our sacred mysteries in such simplistic terms.

On the contrary, I’d suggest that a bilingual mass is any in which a good faith effort is made to draw the communities at hand into the sacred mysteries by virtue of not just the language employed, but the experience in real time — via the visuals, sincerity and warmth of expression, the sounds, melody, harmony, instrumentation, rhythms, tempo, vocal style and delivery, etc. These all play a part in making one feel at home in prayer. In essence, we should be talking about facilitating a bicultural experience of prayer, not merely a linguistic fulfilling of the rite’s texts and rubrics.

Variation in Application

A bilingual mass might include (but is not limited to), mass texts and readings in varying languages, a homily skillfully rendered in a way that is seamlessly woven through intertwining narratives, music selections that are both bilingual and monolingual, musical arrangements and playing that touch the heart beyond lyrics, and visual elements such as worship aids or projection that play a practical role while lending a sensory counterweight to aural elements. Above all, a successful bilingual mass exudes a profound level of hospitality at every corner.

For some communities, a bilingual mass might see some of the spoken mass texts and preaching done bilingually, but the music entirely in Spanish. In other communities, you might find the spoken texts mostly in Spanish, but the music more bilingual-minded, even including English-only songs. Still other communities might incorporate some different blend of linguistic treatment as their norm. In communities with immigrant populations, the primary language of the community may be Spanish, but the presence of younger generations may introduce some openness to English throughout. Conversely, the desire among Latinos to want to connect with their heritage, including its “sound,” may drive English-speaking Latinos (even non-Spanish-speaking ones) to attend a mass that is Spanish-leaning in text and/or character.

Recall that the church already gifts us with vocabulary that transcends culture. The words “Alleluia” and “Amen,” preserved and handed down from their Hebrew origins, are inherently multicultural to begin with. Additionally, creative use of the original Latin (or sometimes Greek) language of our Roman rite in bilingual liturgies can also be a unifying means amidst our diversity.

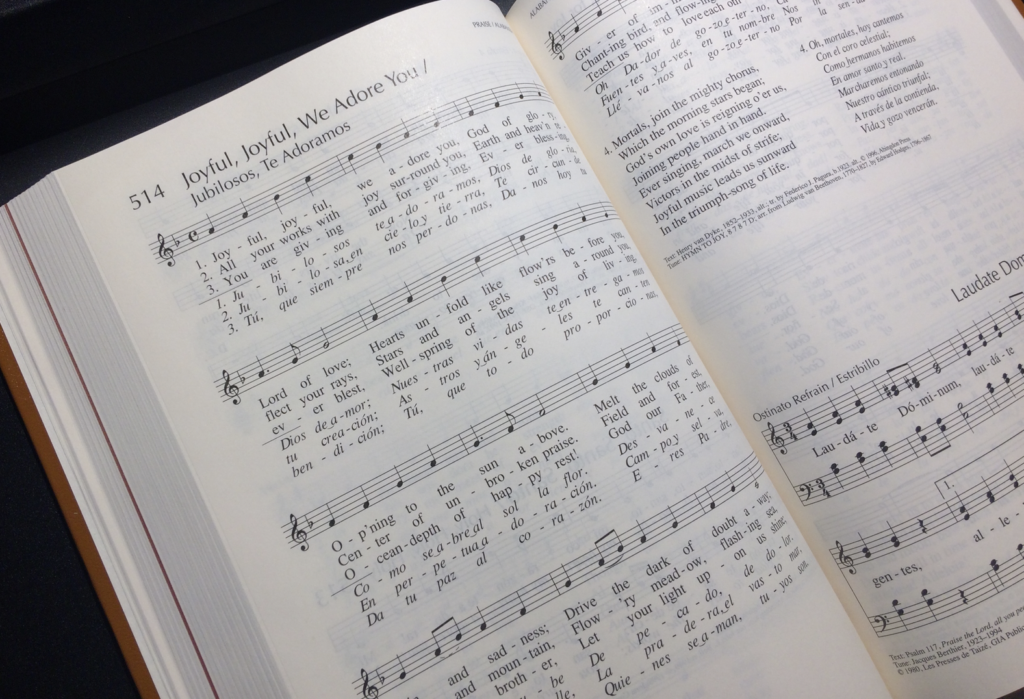

Attention to Context

Context is also a factor. Attuned to the pastoral judgment in the document Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship, certain types of musical pieces and/or linguistic treatments might work better in some celebrations than in others. In a diocesan-level liturgy, for example, where the use of strophic hymns might be normally expected, singing some of those hymns’ stanzas in Spanish might be effective — that is, for “the actual community gathered to celebrate in a particular place at a particular time” (STL, 130). Especially since there now exists good, poetic translations of English-language hymns (thanks, in great part, to our protestant brothers and sisters), inclusion of such a translated hymn could be meaningful and appropriate to either language group. A tune like “Hymn to Joy” comes to mind, whose melody is recognized across English-speaking and Latin America. This same piece or treatment, however, might not be as applicable for a Sunday liturgy at a parish where hymnody is seldom used or whose communal expectation is for more recently-composed Spanish or bilingual selections.

Music planners must also be attentive to the linguistic treatment of the mass ordinary (Kyrie, Gloria, Alleluia, Sanctus, etc.) and responsorial psalm as central to the experience of bicultural prayer.

All Bilingual, All the Time?

An important piece of advice is not to presume that just because a celebration is labeled bilingual, all of the music selections must therefore be bilingual, too. Bear in mind that the bilingual repertoire published in the last few decades serves a valuable purpose, but these compositions are meant to supplement, not supplant, the vast treasury of sacred music each culture has to offer. An overall design to the “flow” of language elements, whether monolingual or bilingual, is more important to the effectiveness of the prayer than is a de facto application of newly-composed bilingual music.

Bilingual liturgies could and should include a variety of genres and instrumentations, from classical to chant to folkloric and contemporary. A myriad of styles and musical forms exists within both the English-language and Spanish-language repertoire. These are to be explored and applied with the understanding that music speaks in a way that words alone cannot. The power of music on the ears of the faithful to uplift and transport them to a place of “at home” is difficult to define but cannot be denied. When extrapolated in creative ways, this thinking could invite a polyphonic motet in Spanish alongside a huapango in English! An open mind to this reality counters the misinformed but oft-prevalent thinking among well-intentioned planners that Hispanic music must always be mariachi style.

Key Resources

Many of these observations may resonate with your own experience or approach. Or not. The premises upon which these observations are based could be vastly different from what you see as your reality. That’s the nature of this ministry. We’re all still discovering, from the trenches on up through the hierarchy. Note that the U.S. Bishops now offer Guidelines for a Multilingual Celebration of Mass on their website. These are generally accepted as good starting points by liturgy planners, but, in the absence of official mandate, cannot viewed as definitive (nor should they be, given the ever-evolving nature of multicultural worship and perils of a one-size-fits-all approach). Of the little academic work that has been done in this field, special mention should be given to the resource Liturgy in a Culturally Diverse Community: A Guide by Rev. Mark Francis (published by the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions), the successor to his earlier, pioneering Multicultural Celebrations: A Guide. This was the first resource in the U.S. to really frame the issues and offer practical solutions, laying the groundwork for practitioners such as you and me.

In closing, I contend that a bilingual liturgy is one that is planned and executed with good intentions, and that has the net effect of welcome. The point is not to subject the participants to some kind of forced, awkward linguistic handshake, but rather that the unity gained by partaking of another’s expression of prayer far surpasses that which is lost by giving up the momentary comfort of one’s native tongue.

¡Que cantemos Amén! Let the church sing Amen!

Welcome • Bienvenidos a ¡Cantemos Amén!

Musings in Hispanic Music Ministry

Welcome! ¡Bienvenidos! These days, there’s many excellent forums to be found on the topic of Hispanic music ministry. There’s also many wonderful minds contributing to the important dialogue on liturgical music and bilingual liturgy. What a privilege to add my voice to theirs… though it is only one among many who are collectively trying to find our way in this new reality.

My own ministerial journey, which began over three decades ago, has taken me from suburban Detroit “folk” masses to inner-city Spanish masses in Chicago, from diocesan liturgies in borderland Texas to impressive large-scale gatherings in cathedrals, arenas, stadiums, and conference ballrooms across the country. This blessed adventure even includes unexpected involvement in papal visits and saintly celebrations. I’ve seen so much along the way, not to mention the unique perspective I’m afforded by the editor’s desk where I sit. But in the scheme of things, I also realize I’ve seen very little. There’s so much more “out there.”

For that reason, I’m the first to admit I don’t have all the answers. There’s a part of me that questions regularly if I really know what I’m doing at all. In all honestly, I don’t. I can’t. And I would venture that none of us in this field could legitimately call ourselves “experts.” Bilingual music and liturgy as we know it in this country is a relatively new phenomenon. We are still foraying unknown waters, making new discoveries, and trying new approaches. Years ahead, we’ll look back on this period and, with the benefit of hindsight, affirm what we got right and reject or revise that which we didn’t. When it comes to bilingual music and liturgy, we still find ourselves in a time of trial and error, with the latter expectedly in abundance.

As I always preface in my workshops, there does not yet exist a higher institution of learning doctorate degree in bilingual liturgy or multilingual liturgical music; there are no individuals out there with a Ph.D. in this field (that I know of) to serve as authoritative experts on such things. I, like many of my colleagues doing this work, am simply a practitioner who has amassed some wisdom in pastoral experience, but who is also very much still learning and open to new discoveries and discourse.

There’s astoundingly so much to explore when it comes to bilingual Spanish-English liturgy. For some communities, the very notion of attempting to meld languages in a liturgical context is a source of anxiety and trepidation. For others, it’s simply second nature. Wherever you find yourself on the spectrum of parish bilingualism, know that in ¡Cantemos Amén!you have a page that seeks to equip you with pastoral insights to help you better engage in this ministry.

For my part, every time I see what’s being done in a different corner of this ministerial world, it keeps me yearning for more. I relish the opportunity to reflect on it all within these pages. So when it comes to matters concerning this exciting world of Hispanic music ministry, I look forward to journeying this path with you, my fellow ministers, filled with wonder and fervor for God’s amazing works.

Hasta pronto… till next time…

¡Que cantemos Amén! Let the church sing Amen!

Why Do We Sing?

By: Diana Kodner Gokce

Explore Sing Amen

Looking for more great resources, articles, podcast, and more throughout all Sing Amen blogs? Search through the site here.

Search By Category

Search Archives